This article was co-authored by Matt Garcia. Matt Garcia is an experienced phlebotomist in Vancouver, Canada. He holds a Diploma in Medical Laboratory Assistance and is certified under the British Columbia Society of Laboratory Science. He previously worked in a high-volume outpatient lab and is currently employed in an acute care hospital and Level III trauma center in downtown Vancouver.

This article has been viewed 45,640 times.

Drawing blood for laboratory analysis is most often a routine and uneventful procedure. But since each patient's medical condition varies, so does their veins. This is a general guide for troubleshooting a venipuncture scenario in which blood flow is not initially established upon needle insertion. Although the skill set and procedures may apply to both instances, this content is primarily aimed towards venous blood collection using evacuated tube systems (e.g. BD Vacutainer®), rather than IV catheter insertions.

Steps

Redirecting the Needle

-

1Back the needle out until the bevel is just below the skin. This preliminary action allows you to safely adjust the needle's position. Be careful not to withdraw the needle completely or else you risk losing the tube's vacuum and starting a hematoma when the bevel exits the skin.

-

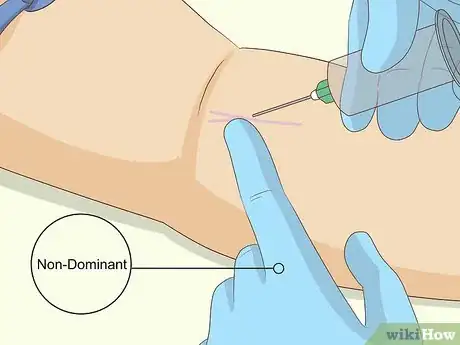

2Palpate the vein using your non-dominant index or middle finger. The goal is to locate the vein in relation to your needle.

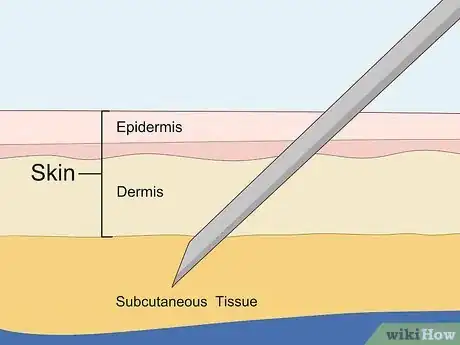

- Remember that veins should ideally feel bouncy. Hard and dense structures may be nerves or tendons. Subcutaneous tissue feels squishy and muscle feels hard. If a vein feels hard, it may be scarred or sclerosed.

- Warning: Make sure you are confident that the structure you're palpitating is indeed a vein. Inadvertently nicking a nerve causes intense pain. Additionally, a hematoma may compress the nerve and lead to long-term damage.

Advertisement -

3Slowly adjust the needle's angle and position to line it up with the vein.

- Warning: Do not make lateral (side-to-side) movements with the needle. This is very painful, risks damage to underlying structures, and widens the needle hole to prolong bleeding time.

-

4Anchor the vein as hard as you can. To do this, position your non-dominant thumb slightly inferior to the vein and pull the skin and subcutaneous tissue downwards taut. This stabilizes the vein to prevent it from rolling.

- Elderly patients often have fragile skin and veins that roll quite easily, When a vein rolls, the needle tends to push the vein aside rather than penetrating through. Therefore, your anchor should be gentle but firm to prevent the vein from moving away from you.

- Warning: Some phlebotomists use a method of anchoring called the "C-hold", in which the index finger pulls upwards superiorly while the thumb pulls downwards inferiorly. While this may be effective in some difficult draws, the risk of a needlestick injury is higher if the patient has a withdrawal reflex and the needle recoils back into your finger.

-

5Advance the needle back further into the skin, watching for blood flow or a flashback. Observe the patient and stop if he/she feels unbearable pain. If you establish blood flow, fill your tubes in the correct order of draw while keeping a stable anchor.

Tip: In spite of a difficult draw, remember to invert your tubes. This is especially important when collecting EDTA (lavender top) or heparin (green top) tubes. Whole blood specimens may not be able to be analyzed if microscopic clots are present.

Troubleshooting Specific Scenarios

-

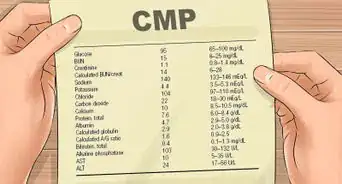

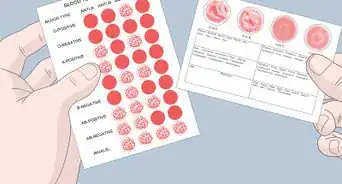

1Check your tube. Blood may not flow sufficiently if you are using an expired, damaged, or dropped tube due to an inadequate vacuum. Check the tube to make sure it is properly positioned in the holder and the inner needle has penetrated through the rubber stopper. Maintain control of the needle when changing tubes.

Tip: If you realize you've collected in the wrong order of draw, remove the tube, insert the correct one, fill it halfway before discarding it, then insert a new tube and fill it completely. Discarding the first set minimizes the effects of any potential additive contamination.

-

2Troubleshoot an incorrect needle position. Although the above section describes the basic steps to redirect a needle, you may need to perform slightly different manoeuvres to correct needle position as described below.

- Needle not inserted far enough: the bevel is in the skin or subcutaneous tissue and has not penetrated the vein. This is a common occurrence when drawing from obese patients. To correct this issue, slowly advance the needle forward.

- Needle is partially or completely through the vein: the bevel penetrates the posterior wall of the vein. A small spurt of blood may appear in the hub as the bevel travels through the vein, but no blood flow is established. This happens when the needle is advanced too far, too quickly, or at too steep of an angle. A bevel that is partially or completely through the vein has the potential to cause a hematoma when blood leaks out of the vessel into the surrounding tissues. To correct this issue, anchor the vein and withdraw the needle slightly until blood flows..

- Needle is only partially in the vein: the bevel is beneath the skin and has begun to penetrate the vein, but not completely. Blood flow may be very slow. To correct this issue, anchor the vein and slightly advance the needle.

- Needle is against the vein wall: the bevel is pressed against the wall of the vessel, impairing blood flow. This may happen if there is a bend or fork within the vasculature. To correct this issue, either withdraw the needle slightly or rotate the assembly a quarter-turn.

- Needle is in contact with a valve: the bevel is stuck in a venous valve, impairing blood flow. A subtle vibration or buzzing sensation may be felt as the valve attempts to open and close. This may happen if there is a bend or fork within the vasculature. To correct this issue, withdraw the needle slightly.

- Needle is beside the vein: the bevel pushed and slipped past the vein rather than penetrating the wall, a phenomenon known as "rolling". This most often occurs when the vein isn't securely anchored and taut. To correct this issue, hold a firm anchor and attempt a redirect.

-

3Recognize when a vein has collapsed. The vein's walls constrict and draw together, stopping blood flow. This can occur when the tube's vacuum is too strong, or when the tourniquet is tied too tight or too close to the venipuncture site or removed altogether.

- If you are using a butterfly, try to retie the tourniquet around the patient's arm to increase pressure and re-establish blood flow.

- You may also remove the tube, wait a few seconds for blood flow to resume, and then engage a short drawtube.

Preemptive Measures to Increase Success

-

1Optimize patient positioning. If drawing from the antecubital fossa, ensure that the arm is fully extended to gain maximum exposure. A bend at the elbow may affect your ability to palpate a vein.

- Use pillows or foam wedges to elevate the arm and help with extension.

- If the patient is sitting in a phlebotomy chair, make sure they are sitting upright with their back against the chair. Adjust the height and swivel the chair to ensure your body is in line with the vein.

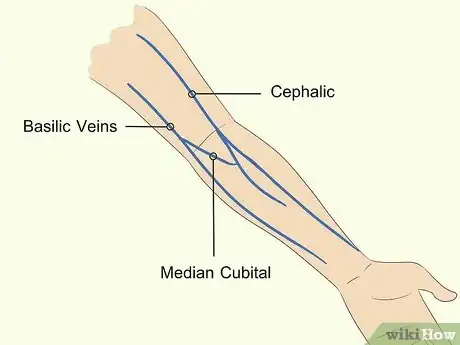

- Try rotating the arm to better expose the cephalic or basilic vein.

Tip: Lowering the arm below the level of the heart may help to engorge the vessels.

-

2Be mindful of your tourniquet. Ideally, it should be placed 3-4 finger-widths above the planned venipuncture site. The tourniquet should be tight enough to engorge the vein, but not so tight as to cut off arterial circulation.

- Keep in mind that elderly patients often have fragile veins. Too tight of a tourniquet may cause the vein to collapse upon needle insertion.

-

3Assess the site carefully. Venipuncture is typically performed at the antecubital fossa (on the median cubital, cephalic, and basilic veins), or on the dorsum of the hand.

- Each time a vein is accessed with a needle, scar tissue forms as part of the body's healing process. Over time and with several repeated punctures, significant amounts of scar tissue builds up. This makes every subsequent poke harder and harder because scar tissue is more fibrous and tougher to puncture.

- Look for visual clues which may help assess the patient's condition. Patches of purple or yellow may suggest bruising after a recent venipuncture. Scan the skin for lines of blue indicating a prominently visible vein. Track marks are not only found on IV drug users, but also on chronically ill patients requiring repeated vascular access and blood draws and may be a sign of an anticipated difficult draw.

- Be methodical in your search for a vein. Start with the arm closest to you and palpate the antecubital fossa. Feel for the median cubital first, the cephalic vein second, and the basilic vein third. Switch to the other arm if you can't find anything. Look at the dorsum of the hand as a last resort.

Tip: Patients who need regular bloodwork (e.g. INR for patients on warfarin) are often knowledgeable on the veins that are most likely to work.

-

4Apply heat to the site to make the veins more prominent. Check to see if your facility stocks infant heel warmers commonly used for capillary punctures. If not, a hot towel or glove filled with water may help. Leave this on the site for 5 minutes before assessing.

-

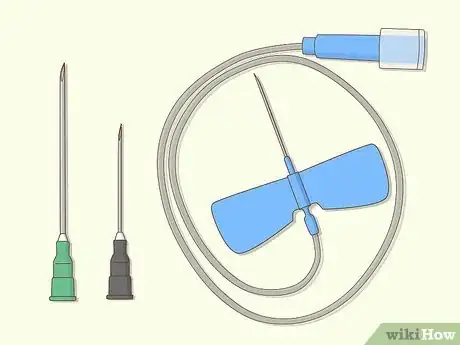

5Use the most suitable needle. Needle choice should be based on the type and number of tubes to be collected, the condition of the vein, the perceived degree of anticipated difficulty, and your own clinical judgment.

- A 21-gauge needle (e.g. BD Eclipse green-capped) is used for most routine and uncomplicated venipunctures. 23-gauge needles (e.g. BD Eclipse black-capped) have a smaller diameter and may be more suitable for smaller veins.

- Butterflies are incredibly valuable tools for tackling difficult draws, owing to their precision, shorter shaft length, and maneuverability. By holding the needle either by the plastic wings or the hub, phlebotomists can achieve a shallower angle, typically 10-15 degrees.

Tip: When using a butterfly and sodium citrate is the first to be collected in the order of draw, a discard tube must always be filled first to purge the air from the tubing. Failure to do this results in an unequal blood-to-additive ratio, making the specimen unsuitable for analysis.

-

6Consider using short draw tubes. These tubes are smaller in volume and therefore have a weaker vacuum to reduce the risk of the vein collapsing. Short draw tubes prove useful when drawing blood from elderly and pediatric patients, as well as from hand veins.

Tip: BD Vacutainer® tubes use a translucent stopper to identify short draw variants. EDTA and sodium citrate tubes should still be filled to the marked fill line to ensure a correct blood-to-additive ratio.

Warnings

- Guidelines established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) dictate that a phlebotomist shall not attempt a venipuncture more than two times, and a maximum of three attempts shall be undertaken on a patient. After the third attempt, further medical directions must be sought with the attending physician before proceeding.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Avoid excessive probing ("fishing"). Blindly maneuvering the needle within the skin is painful to the patient and you run the risk of hitting a nerve, tendon, or artery. You should not perform this technique unless you are certain that the needle is in the immediate vicinity of the vein.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Drawing blood from major vessels (e.g. jugular) or a central venous catheter is out of the scope of practice of a certified phlebotomist and should only be performed by a physician or advanced nurse.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Consult the nursing unit or your facility's resources prior to drawing from an IV or PICC line or performing venipuncture on an arm with an IV line in place. Blood samples drawn from an IV line should be documented and analyzed with care. Concentrations of fluids and medications could affect baseline test results. Additionally, blood samples should not be taken on an arm with a fistula used for dialysis treatments.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Stop the procedure and remove the needle if:

- An artery has been punctured (characterized by bright red, pulsating blood)

- A nerve has been nicked (patient may complain of an electrical sensation up and down the limb)

- A hematoma starts to form (a bubble under the skin starts to rapidly appear at the site)

- The patient loses consciousness or starts seizing

- The patient requests you to stop

⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- McCall, R. E., & Tankersley, C. M. (2016). Phlebotomy Essentials (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. (2017). Collection of Diagnostic Venous Blood Specimens (7th ed.). Wayne, PA.

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...