This article was co-authored by Liana Georgoulis, PsyD and by wikiHow staff writer, Janice Tieperman. Dr. Liana Georgoulis is a Licensed Clinical Psychologist with over 10 years of experience, and is now the Clinical Director at Coast Psychological Services in Los Angeles, California. She received her Doctor of Psychology from Pepperdine University in 2009. Her practice provides cognitive behavioral therapy and other evidence-based therapies for adolescents, adults, and couples.

There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 15,356 times.

There’s no easy way to deal with self-harm, especially if a relative, friend, or acquaintance is suffering from afar. Despite popular belief, self-harm isn’t a ploy for attention or a suicide attempt, but rather a physical sign that someone is dealing with really severe, upsetting feelings or circumstances.[1] If someone you care about is dealing with self-harm issues, they’re not alone—17% of minors resort to self-harm, as do 15% of college students and 5% of adults.[2] While there’s no instantaneous way to guide someone to a safer, healthier path, you can do your best to offer support, help, and comfort to those who need it.

Steps

Taking Direct Action

-

1Focus on treating the injury first if it’s serious. People can self harm in different ways, like cutting, burning, or swallowing pills and other unhealthy substances. If the person is bleeding, apply direct pressure to the wound until the bleeding stops. If the person is dealing with a burn, encourage them to rinse off the affected skin with cold water for 10 minutes. If you think the person is in immediate danger, don’t hesitate to call emergency medical services.[3]

- The best thing you can do in an emergency is call for help. Severe bleeding, burns, and any kind of overdose are best handled by medical professionals.

-

2Watch for potential warning signs of self-harm. Unfortunately, self-harm manifests uniquely in different people. Be on the lookout for frequent cuts, wounds or scars, and/or weak explanations for these injuries. Additionally, see if the person is wearing longer sleeves or pants in uncomfortable weather. Individuals who self-harm may be a bit moodier or irritable, as well.[4]

- If you live with the individual, you may notice blood-soaked tissues or towels lying around.

- Someone who self-harms may claim that they “tripped” or “bumped into something” to excuse their injuries.

Advertisement -

3Ask the person what their triggers are. Triggers are an event or feeling that motivate someone to self-harm. If you understand why and how a person is hurting, you may be better-equipped to help them.[5]

- For instance, a person may be triggered to self-harm if they’re reminded how lonely and empty they feel inside.

- Another person may be triggered by events that remind them of a traumatic incident.

-

4Offer safer replacements for self-harm. Self-harm can be a difficult habit to break, and it may be difficult to know how or where to start. If the person wants to recover, you can suggest some harmless activities they can try instead of cutting, like placing an ice cube on their skin, snapping a rubber band, or drawing red marks instead of physically cutting. While these solutions aren’t perfect, they may be a good stepping stone.[6]

- For instance, if the person tends to self-harm around their wrists, you can encourage them to rub an ice cube over their wrist whenever they’re tempted to self-injure.

-

5Teach them different coping mechanisms. Ultimately, self-harm is a coping mechanism for a really tough problem—for some people, it’s a way to deal with intense feelings, while others use self-harm to calm themselves down. With this in mind, suggest different, healthy alternatives that can help them release and channel their emotions that won’t hurt them in the process.[7]

- If someone is experiencing really painful emotions, encourage them to draw or paint with red colors. They can also channel their feelings into poetry, or write their thoughts down and rip up the paper afterwards.

- If a person uses self-harm to calm down, invite them to snuggle with a pet, bundle up in a blanket, listen to relaxing music, or take a hot bath.

- If someone is self-harming to help feel more connected, encourage them to take a cool shower, chew something pungent (e.g., a chili pepper, citrus peel), or log onto a self-help chat room.

- If they’re self-injuring to vent their feelings, remind them to do some intense exercise, grip a stress ball, rip up some paper, or bang some pots and pans around.

- You can find many coping alternatives here: https://www.adolescentselfinjuryfoundation.com/things-to-do-besides-self-harm.

Offering Emotional Support

-

1Maintain a compassionate attitude when you speak with the person. There’s no easy way to bring up self-harm, especially if you’re mentioning it for the first time. Don’t worry about following an exact script—instead, stress that you care about the person and that you‘re there to support them. Acknowledge that this is a really tough thing to talk about, and that you’ll support them whenever and wherever they need you.[8]

- Try to come from an honest, genuine place—you want to communicate love and concern in a way that's straight to the point, but not judgmental. It's really important to let the person know that you're there for them.[9]

- Give yourself plenty of time to talk with your friend, family member, or acquaintance. This is a heavy topic, and not something you can talk about in between classes or in a passing conversation.

- You can say something like: “Hey. I’ve been noticing some cuts and bruises on your arms a lot, and I just wanted to check in and make sure that you’re okay. If there’s anything wrong, please know that you can talk to me.”

- It’s okay if you don’t know the right thing to say! What matters most is that you’re offering compassion and support to someone who’s struggling.

-

2Accept that the person may not want to talk. Self-harm is a really tricky topic to cover, and you may not make much progress in a basic conversation. At the end of the day, remember that it’s up to your friend, relative, or acquaintance to decide if they want help or support. If the person isn’t very receptive, don’t take it personally—self-harm is a tough topic to talk about, and the person may need more time to sort out their own feelings.[10]

- If someone shuts down your offer for help, say something like: “I understand, and I respect your privacy. However, please know that I’m here for you if you need anything.”

-

3Continue offering support to them. After the initial conversation, check in with the person and see how they’re doing. Make it clear that you’re still there for them, and encourage them to talk with a professional so they can really get the help they need. You can also lend a hand by helping them figure out what triggers their negative emotions and desire to self-harm.[11]

- For instance, if a person sees a couple in the hallway at school, they may be overwhelmed and triggered by a feeling of loneliness.

- A person refusing your offers to help doesn’t mean that they still don’t need it.

-

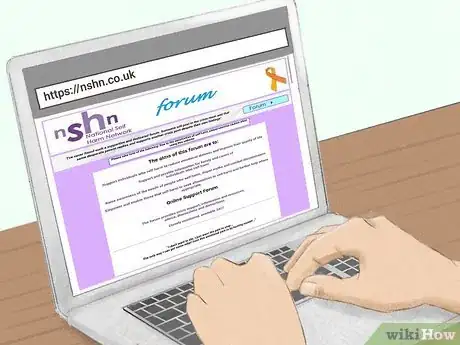

4Direct the person to supportive phone lines and websites. It’s great that you’re offering a listening ear, but you shouldn’t be the only lifeline. Remind your friend, relative, or acquaintance that there are a lot of resources available for people who are struggling with self-harm. Direct them to some phone lines or chat rooms that you feel may be helpful.[12]

- Self-harm is usually an indication that a person is feeling quite a lot of emotional pain, so they'll likely need continued support to overcome this problem.[13]

- For instance, you can direct them to a National Self Harm Network forum, or encourage them to email an organization like Harmless for more information and support.

- For direct help, tell them to text 741741, which is a crisis text line.[14]

-

5Suggest that they speak with a therapist. Remind the person that while you’ll always be there for them, you can’t offer them the same professional advice that they’d get from a therapist. Encourage your friend, family member, or acquaintance to try out Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Problem Solving Therapy, or Dialectical Behavior Therapy. All of these therapies work to improve your thoughts and behaviors in a healthy, constructive way.[15]

- If they don’t have access to therapy, lead them to a helpful outreach site, like: http://sioutreach.org.

- Talking to a therapist can help the person understand what feelings are coming up and why. That can be really empowering in terms of moving forward in a new, different way.[16]

-

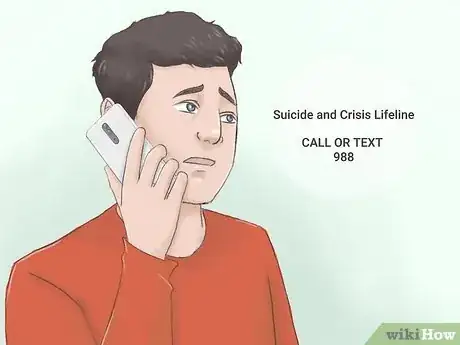

6Encourage them to call for help if they’re feeling suicidal. Remind your acquaintance or loved one that suicide is not the answer, and that there are a lot of people who care about and love them. Suggest that they call a hotline instead—these numbers are managed by experienced counselors who can help talk them through their intense emotions.[17]

- In the US, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. In the UK, call 116 123.

Avoiding Harmful Language and Behavior

-

1Don’t praise someone for self-harming. Conversations about self-harm are uncomfortable, and it can be really tough to manage a conversation. Being supportive and compassionate is important, but don’t say anything that somehow praises or justifies their habits. Focus on acknowledging their pain instead of uplifting and encouraging it.[18]

- For instance, don’t say something like: “I wish I was as strong as you.” Instead, say: “You must be going through so much pain right now. I’m always here to listen if you need it.”

-

2Refrain from making threats or ultimatums. Self-harm can be a scary thing to think or talk about—however, it’s also a very scary, emotional experience for the person participating in it. Expressing disappointment or making idle threats isn’t going to change anything. Instead, you’ll probably make the person feel more upset and isolated. Try your best to keep a compassionate, supportive attitude during your conversations.[19]

- Never say something like: “If you don’t stop self-harming, I won’t be your friend anymore” or “You’re just hurting yourself for attention.” Instead, say something like: “You mean a lot to me and I want you to be happy and healthy. Do you want me to help you find a good therapist?”

-

3Don’t promise to keep their “secret.” Self-harm is very serious—while it’s important to maintain trust, you don’t want to put someone else’s life in danger. Feel free to share your worries with a trusted adult or person who is able to help. Even if they don’t intend to commit suicide, they could end their life unintentionally through a self-harm attempt.[20]

- For instance, you can bring your concerns to a guidance counselor at school, or a Human Resources representative at work.

- If you suspect that a sibling or other loved one is self-harming, confide in a parent, guardian, or other trusted relative for help.

Expert Q&A

-

QuestionHow can I support someone who's self-harming?

Liana Georgoulis, PsyDDr. Liana Georgoulis is a Licensed Clinical Psychologist with over 10 years of experience, and is now the Clinical Director at Coast Psychological Services in Los Angeles, California. She received her Doctor of Psychology from Pepperdine University in 2009. Her practice provides cognitive behavioral therapy and other evidence-based therapies for adolescents, adults, and couples.

Liana Georgoulis, PsyDDr. Liana Georgoulis is a Licensed Clinical Psychologist with over 10 years of experience, and is now the Clinical Director at Coast Psychological Services in Los Angeles, California. She received her Doctor of Psychology from Pepperdine University in 2009. Her practice provides cognitive behavioral therapy and other evidence-based therapies for adolescents, adults, and couples.

Licensed Psychologist Always start by coming from a real, honest, genuine place, and communicate concern and love in a way that's concise but not judgmental. Sometimes, you have to challenge people so you can express your concerns and how much you care for them.

Always start by coming from a real, honest, genuine place, and communicate concern and love in a way that's concise but not judgmental. Sometimes, you have to challenge people so you can express your concerns and how much you care for them. -

QuestionWhat should I do if I think my sibling is going to hurt themselves?

Padam Bhatia, MDDr. Padam Bhatia is a board certified Psychiatrist who runs Elevate Psychiatry, based in Miami, Florida. He specializes in treating patients with a combination of traditional medicine and evidence-based holistic therapies. He also specializes in electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), compassionate use, and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Dr. Bhatia is a diplomat of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and a Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association (FAPA). He received an MD from Sidney Kimmel Medical College and has served as the chief resident in adult psychiatry at Zucker Hillside Hospital in New York.

Padam Bhatia, MDDr. Padam Bhatia is a board certified Psychiatrist who runs Elevate Psychiatry, based in Miami, Florida. He specializes in treating patients with a combination of traditional medicine and evidence-based holistic therapies. He also specializes in electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), compassionate use, and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Dr. Bhatia is a diplomat of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and a Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association (FAPA). He received an MD from Sidney Kimmel Medical College and has served as the chief resident in adult psychiatry at Zucker Hillside Hospital in New York.

Board Certified Psychiatrist Contact a psychiatrist for a risk assessment—they'll look for acute risk factors that might indicate whether someone could hurt themselves or someone else. That's crucial to understanding what level of care that patient needs.

Contact a psychiatrist for a risk assessment—they'll look for acute risk factors that might indicate whether someone could hurt themselves or someone else. That's crucial to understanding what level of care that patient needs.

Warnings

- Call emergency services if you suspect someone is attempting suicide. If you suspect someone is in crisis, encourage them to call a helpline at 988 in the US (they can also text this number), or 116 123 in the UK.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ https://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/cutting-and-self-harm.htm

- ↑ https://www.apa.org/monitor/2015/07-08/who-self-injures

- ↑ http://www.lifesigns.org.uk/first-aid-for-self-injury-and-self-harm/

- ↑ https://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/cutting-and-self-harm.htm

- ↑ https://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/cutting-and-self-harm.htm

- ↑ https://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/cutting-and-self-harm.htm

- ↑ https://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/cutting-and-self-harm.htm

- ↑ https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/truth-about-self-harm

- ↑ Liana Georgoulis, PsyD. Licensed Psychologist. Expert Interview. 7 February 2020.

- ↑ https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/truth-about-self-harm

- ↑ https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/March-2018/How-to-Respond-to-Self-Harm

- ↑ https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/self-harm/

- ↑ Liana Georgoulis, PsyD. Licensed Psychologist. Expert Interview. 7 February 2020.

- ↑ https://www.crisistextline.org/topics/self-harm/#pass-741741-on-to-a-friend-8

- ↑ https://www.suicideinfo.ca/resource/self-harm-and-suicide/

- ↑ Liana Georgoulis, PsyD. Licensed Psychologist. Expert Interview. 7 February 2020.

- ↑ https://www.psychreg.org/suicide-hotline-numbers/

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/friend-cuts.html

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/friend-cuts.html

- ↑ https://www.suicideinfo.ca/resource/self-harm-and-suicide/

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/friend-cuts.html

- ↑ https://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/cutting-and-self-harm.htm