This article was written by Jennifer Mueller, JD. Jennifer Mueller is an in-house legal expert at wikiHow. Jennifer reviews, fact-checks, and evaluates wikiHow's legal content to ensure thoroughness and accuracy. She received her JD from Indiana University Maurer School of Law in 2006.

This article has been viewed 28,747 times.

When you hear the word "assault," you may think of the crime, but you also can sue someone in civil court for assault. Civil charges of assault are completely separate from any criminal charges, and you may get money from an assailant for civil assault even if he is found not guilty of criminal assault. This is so because although the elements of both the crime and the tort are essentially the same, the burden of proof is different. An assailant is liable for monetary damages for civil assault if you prove by a preponderance of the evidence that he assaulted you and caused the damages you claim – a standard much more lax than the criminal standard of beyond a reasonable doubt.[1] [2]

Steps

Proving an Intentional Threat

-

1Describe the events that transpired. The immediate events that constituted the assault may themselves provide clues to your assailant's intent.

- Not only must you prove the assailant intended to harm you, but you also must prove he was capable of doing so.

- Contrary to popular belief, a person does not have to physically hurt you or even touch you to be liable for assault. However, if you were not physically harmed, you must demonstrate that the person intended to harm you.[3]

- An accident won't make a person liable for assault, even if he actually did hurt you – you must be able to prove that he meant to hurt you, regardless of whether he actually did.

- Generally threatening words won't necessarily put someone on the hook for assault. Rather, those words must be accompanied by some sort of action that makes it clear he intends to follow through with those words by using physical force against you.[4]

- Conditional statements or vague threats of retribution at some point in the future typically won't rise to the level of assault either.[5] For example, if someone says to you "If you come back here again, I'll smash you against the wall!" that probably wouldn't constitute assault, even if you believe he has every intention of smashing you against the wall. By his own words, the assault would only happen if you returned to the location.

- You also must be able to demonstrate that the person had the ability to cause whatever harm he intended.[6] For example, a small child flailing madly while held at arm's length by his older brother may intend to hurt his brother, but as he can't reach him he can't be said to have the ability to cause the harm.

-

2Talk to any witnesses of the assault. Witnesses may be able to expose different angles of the events that further expose your assailant's intent.

- Witnesses also may know things that happened either before or after the assault itself that you didn't know about. Statements or actions made by the assailant either in the build-up or the aftermath of the assault may serve to further explain his intent.

Advertisement -

3Research your assailant's past. If your assailant has a history of assaulting others, this might be helpful in proving he intended to assault you.

- For example, if you knew that Tommy tended to punch first and ask questions later, if Tommy took a swing at you, it stands to reason that he intended to assault you – either he meant to punch you and missed, or he knew his reputation and wanted you to be afraid he would punch you.

-

4Consider calling reputation or character witnesses. People who know the assailant well can offer additional insights into his behavior both before and during the altercation.

- Statements made before the event could offer clues to your assailant's intent, even if you didn't know of them at the time. For example, suppose a mutual friend brought your name up to your assailant a few hours before you crossed paths. Your assailant shook his head and said "Man, next time I see him, I'm going to rearrange his face!" Even if he never hurt you, such statements might indicate he intended to do you harm.

Proving Your Reasonable Apprehension

-

1Make a physical comparison between yourself and your assailant. If your assailant is significantly larger than you, that fact can help demonstrate that your fears or expectations of harm were reasonable.

-

2Describe your assailant's words and body language. Show that what your assailant said or how he acted towards you was intimidating or caused you to fear he would harm you.

- Keep in mind that you don't have to prove your assailant intended to cause you fear – he only needed to intend to commit the act. Your assailant's motive is irrelevant for the purposes of civil assault, as long as your fear or apprehension was reasonable.[7]

-

3Explain any special circumstances. If your assailant was in a position of authority over you or otherwise had power over you, that relationship may cause a higher level of intimidation or fear.

- For example, if the person you've sued for assault was your coach, he was in a position of authority over you. That position of authority may cause him to be more intimidating to you generally than he would be if you encountered him randomly as a stranger on the street.

- Actions from someone with a level of power and authority over other others, such as a coach or a manager, generally will be viewed as more intimidating than if the same action was taken by someone with no relation to the victim.

-

4Have witnesses testify to the reasonableness of your fears. If anyone witnessed the altercation and they also worried you would be harmed, their testimony can help prove your fears were reasonable.

Proving Your Damages

-

1Gather any medical bills and make copies. If you actually were harmed and had a doctor treat your injuries, your assailant is responsible for paying those expenses.

- Medical bills represent a form of compensatory damages, financial losses you incurred as a result of the assault and for which your assailant is liable.[8]

- Typically, a civil assault claim would be made separately from a civil battery claim, which involves physical contact and injury.[9] However, in some states the two claims may be heard together, or civil battery may be included in civil assault.

-

2Gather evidence of any lost wages. If you missed work as a result of the assault, you also can include those lost wages as damages you incurred.

- Lost wages are another type of compensatory damages.[10]

-

3Have friends or family members testify regarding your pain and suffering. Even if you don't have any actual damages such as medical bills or lost wages, you still can get money for your pain and suffering as a result of the assault.

- Even if you can prove no actual damages as a result of the assault, the court may still award nominal damages to acknowledge that your assailant violated your rights.[11]

- Nominal damages typically are awarded in cases where the judge or jury intends to award punitive damages.[12]

- Special damages, such as the need for ongoing psychiatric care as a result of the assault, often require an expert witness such as a psychiatrist to testify to your need for that ongoing treatment.[13]

-

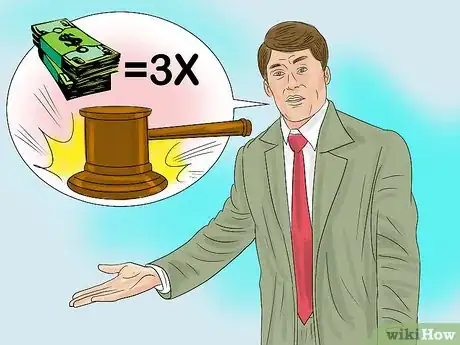

4Argue for punitive damages. Since assault is an intentional tort, you have the right to seek punitive damages against your assailant.[14]

- Intentional torts arise from an intentional act of the defendant rather than the defendant's negligence. The law treats intentional acts differently than negligence, and allows victims to get punitive damages.

- Punitive damages are meant not only to punish your assailant by making him pay for harming you, but also deter others from engaging in similar behavior.

- Depending on the severity of the case, the court may award punitive damages in amounts as much as three times what you could be awarded for regular damages.[15]

- An award of either nominal or compensatory damages is required before you can be awarded punitive damages, since punitive damages are awarded as a multiple of the regular damages awarded.[16]

References

- ↑ http://blogs.findlaw.com/injured/2015/01/how-do-you-prove-assault-in-civil-court.html

- ↑ http://injury.findlaw.com/torts-and-personal-injuries/civil-assault-cases.html

- ↑ http://blogs.findlaw.com/injured/2015/01/how-do-you-prove-assault-in-civil-court.html

- ↑ http://blogs.findlaw.com/injured/2015/01/how-do-you-prove-assault-in-civil-court.html

- ↑ http://blogs.findlaw.com/injured/2015/01/how-do-you-prove-assault-in-civil-court.html

- ↑ http://injury.findlaw.com/torts-and-personal-injuries/civil-assault-cases.html

- ↑ http://www.alllaw.com/articles/nolo/personal-injury/civil-case-criminal-case-after-assault.html

- ↑ http://blogs.findlaw.com/injured/2015/01/how-do-you-prove-assault-in-civil-court.html

- ↑ http://www.alllaw.com/articles/nolo/personal-injury/victims-right-civil-damages-assault.html

- ↑ http://blogs.findlaw.com/injured/2015/01/how-do-you-prove-assault-in-civil-court.html

- ↑ http://blogs.findlaw.com/injured/2015/01/how-do-you-prove-assault-in-civil-court.html

- ↑ http://www.alllaw.com/articles/nolo/personal-injury/victims-right-civil-damages-assault.html

- ↑ http://www.alllaw.com/articles/nolo/personal-injury/victims-right-civil-damages-assault.html

- ↑ http://blogs.findlaw.com/injured/2015/01/how-do-you-prove-assault-in-civil-court.html

- ↑ http://injury.findlaw.com/torts-and-personal-injuries/civil-assault-cases.html

- ↑ http://www.alllaw.com/articles/nolo/personal-injury/victims-right-civil-damages-assault.html