This article was co-authored by Clinton M. Sandvick, JD, PhD. Clinton M. Sandvick worked as a civil litigator in California for over 7 years. He received his JD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1998 and his PhD in American History from the University of Oregon in 2013.

There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 24,917 times.

In the United States, you have a Constitutional right not to testify against yourself. The Fifth Amendment reads, “No person….shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.”[1] This means that you don’t have to testify in court as a defendant. It also means that you don’t have to talk to the police. You must be careful to avoid self-incrimination. Any statement you make, at any time, could potentially be introduced at trial. This includes statements you make when you are not yet a suspect.

Steps

Avoiding Self-Incrimination Before Arrest

-

1Get an attorney. The best thing you could do is get an attorney.[2] If you were involved in a criminal incident, in any way, then you should talk to an attorney, even before the police come knocking on your door. Ask the attorney how you can best protect your rights and get a phone number where you can reach him or her if you are arrested.

- You can find a criminal defense attorney by contacting your local or state bar association and asking for a referral.

- You could also talk to people in your community who have used criminal defense attorneys. However, you might want to hesitate so that no one in the community knows that you were connected in any way with the criminal incident.

-

2Refuse to talk to police. Police might contact you because a witness at the scene of the crime saw you there. The police might not think you are a suspect. Nevertheless, anything you say can later be used against you in court, whether you are a suspect or not.

- Unless you are absolutely innocent, then you should refer the police to your lawyer. You are not required to answer any police questions.[3]

- In some states, you must identify yourself if you are stopped by the police. For example, in Ohio, you must provide your name, address, and date of birth to a police officer when asked.[4] Do not answer any other questions.

Advertisement -

3Ignore promises made by the police. In order to get you to talk, the police might say all kinds of things. For example, they might promise not to use a statement that you make against you. Or they might say, “Hey, you aren’t a suspect, so you have nothing to worry about. Just talk to us and this will go away.” These are empty promises.

- The police do not decide what statements can be used later in a prosecution. The prosecutor will decide what evidence to present to a jury. You should never listen to the police when they try to tell you what will happen in the future.

- Police are allowed to lie to you. For example, a police officer can say that they have fingerprints and DNA evidence that tie you to the crime. The police can lie in the hopes that you will confess.[5] Always refer the police to your lawyer no matter what they say.

- You might feel pressured to talk because you just want this whole situation to go away. However, you cannot argue your way out of being investigated or suspected of committing a crime. If you talk, all you potentially do is dig a hole for yourself.[6]

-

4Don’t talk about the incident with others. Any statement you make to other people can also be introduced at trial. For this reason, you shouldn’t talk to other people about any criminal incident you were involved in.

- Keep a low profile. Your friends might start calling or stopping by, wanting to know what happened. You need to ignore them as best you can.

Avoiding Self-Incrimination After Arrest

-

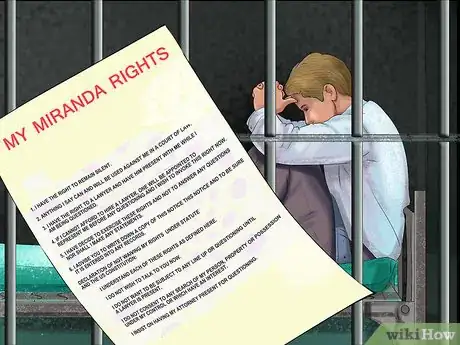

1Listen to your Miranda rights. The Supreme Court requires that police give the four warnings before questioning you. They only have to give these warnings if you are in custody. Remember, however, that any statement made, even when not in custody, can be used against you.[7] The four Miranda warnings are:[8]

- You have the right to remain silent.

- Anything you say can and will be used against you in court.

- You have the right to a lawyer.

- If you can’t afford a lawyer, one will be provided for you.

-

2Say you don’t want to talk to the police. You have to make an explicit request: “I don’t want to talk to you.” You can’t just sit there silently. Without an explicit request, the police can continue to question you.

- The police can also come back after a certain amount of time and ask if you want to talk (unless you requested a lawyer, in which case they can’t re-engage you). You will have to continue to repeat that you don’t want to talk to the police.[9]

-

3Request a lawyer. After stating that you want to remain silent, request a lawyer. You need to be explicit. Don’t just nod your head when the officer says you have the right to a lawyer. Also don’t request a probation officer. Instead, you should say, “I want to talk to an attorney.” When you request a lawyer, the police must stop all questioning.

- The right to a lawyer is a separate right from the right to remain silent. You need to say both. If all you say is, “I don’t want to talk to you,” then the police do not have to interpret that as a request for a lawyer.

- If you have a lawyer, then you should be able to make a phone call to talk to him or her. If you can’t reach your lawyer, then call a family member. Tell them where you are located.

- If you can’t afford a lawyer, then you will need a public defender. You might have to wait days, until your arraignment, before you meet with the public defender.

-

4Avoid chatting with the police. After you request a lawyer, the police can’t approach you to start up questioning again. However, if you reach out to them and start talking about the incident, then they may start questioning you again.[10] For this reason, you should limit what you say to the police.

- You can ask for food or water or to use the bathroom, but that’s it. Don’t engage in small talk with the police.

- If an officer approaches you to talk, repeat that you don’t want to talk and that you want to meet with a lawyer.

Getting Statements Thrown Out of Court

-

1Talk with your lawyer about your interrogation. You might have confessed or made incriminating statements to the police. However, you might be able to prevent the prosecutor from introducing those statements in court. Generally, you can “suppress” the statements if the police made mistakes while questioning you. For example, you could get the statements suppressed if the police made any of the following mistakes:

- The police physically coerced you to confess. Any physical coercion is generally prohibited. The more coercive the touching—such as slapping or punching—then the easier it will be to prove that your statements weren’t voluntary. However, even slight touching, such as grabbing your wrist, could be coercive.

- The police denied you food or water, or otherwise made you very uncomfortable. A court will throw out the statements if the “totality of the circumstances” leads them to believe the interrogation was coercive. Coercion is more than physical coercion. It can also include making you physically uncomfortable. Other factors include your age and intelligence.[11]

- The police didn’t read you all of your Miranda warnings.[12]

-

2Bring a motion to suppress. You can get any incriminating statements thrown out of court by bringing a motion to suppress.[13] In order to win the motion, you have to identify that the police did something wrong when they interrogated you.

- Your lawyer must draft the motion and file it in court. In federal court, and in many state courts, you have to file this motion before trial.[14] [15]

- Your lawyer might not want to draft the motion. Motions usually take a lot of time to write, and your lawyer might be pressed for time. Nevertheless, your lawyer needs to draft and file a motion to suppress. If he or she doesn’t, then you did not preserve the issue for a possible appeal.

-

3Have your lawyer argue the motion. The prosecutor will be allowed to respond to the motion and then the judge will schedule a time to hear argument.[16] If you win, then the prosecutor cannot use your incriminating statements in their case.

- The outcome of the motion might influence whether you want to testify. Talk about this with your lawyer. For example, your incriminating statements might have been the only real proof the prosecutor had that you were at the crime scene. If the statements are suppressed, then you might not want to testify at trial.

-

4Raise the issue on appeal. If you are convicted, then you can appeal your conviction to a higher court. In your appeal, you point out any mistakes you think the judge made.[17] One error might be the judge’s refusal to suppress your statements. If you win your appeal, you can get a new trial.

- With luck, your trial lawyer filed a pre-trial motion to suppress. If not, then the appellate court will review the judge’s decision only under the “plain error” standard. This means the error must have been obvious and probably led to your conviction.

References

- ↑ https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/fifth_amendment

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/questioning-after-claiming-miranda.html

- ↑ https://www.ohiobar.org/ForPublic/Resources/LawFactsPamphlets/Pages/LawFactsPamphlet-21.aspx

- ↑ https://www.ohiobar.org/ForPublic/Resources/LawFactsPamphlets/Pages/LawFactsPamphlet-21.aspx

- ↑ http://truthvoice.com/2015/07/san-diego-defense-attorney-explains-10-ways-cops-are-allowed-to-lie/

- ↑ https://www.ohiobar.org/ForPublic/Resources/LawFactsPamphlets/Pages/LawFactsPamphlet-21.aspx

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/police-questioning-miranda-warnings-29930.html

- ↑ http://www.mirandawarning.org/whatareyourmirandarights.html

- ↑ https://www.ohiobar.org/ForPublic/Resources/LawFactsPamphlets/Pages/LawFactsPamphlet-21.aspx

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/questioning-after-claiming-miranda.html

- ↑ http://constitution.findlaw.com/amendment5/annotation09.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/statements-obtained-police-violate-miranda.html

- ↑ http://criminal.findlaw.com/criminal-procedure/how-to-suppress-evidence.html

- ↑ https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcrmp/rule_12

- ↑ http://nebraskalegislature.gov/laws/statutes.php?statute=29-822

- ↑ http://criminal.lawyers.com/criminal-law-basics/criminal-trials-pretrial-motion-to-suppress.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/appealing-conviction.html