This article was co-authored by Trudi Griffin, LPC, MS. Trudi Griffin is a Licensed Professional Counselor in Wisconsin specializing in Addictions and Mental Health. She provides therapy to people who struggle with addictions, mental health, and trauma in community health settings and private practice. She received her MS in Clinical Mental Health Counseling from Marquette University in 2011.

This article has been viewed 53,797 times.

It can be difficult to talk to one's parents at all let alone about a serious issue such as an eating disorder. Remember, though, that eating disorders are very real and can be very serious and that this is something you should talk to your parents about. Keep in mind that the initial conversation may be somewhat painful, but in the long run it will pay off in the form of receiving your parents' love, advice, and support.

Steps

Preparing for the Conversation

-

1Assess your reasons. Ask yourself why you want to tell your parents you have an eating disorder. Is it so that they will treat you differently? Is it to ask for their support? Or do you need to ask if they will pay for you to see a mental health professional to help you overcome your disorder?

- When you have a sense of what your goals are, you can more readily steer the conversation in the way that you want it to go.

-

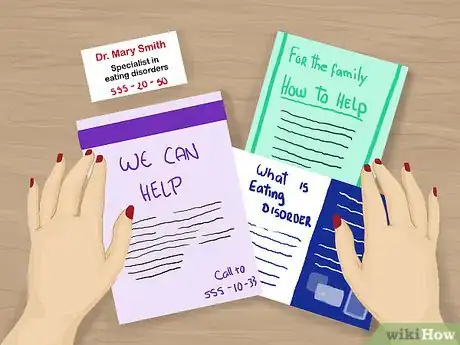

2Prepare materials. Collect some reading material that explains what eating disorders are and how they are addressed. The material should provide details about what people usually do in this matter. Print something off the internet or, if you have one, ask your counselor for some relevant pamphlets.

- Your parents might not know much about what eating disorders are, so this way you can educate them with the most up-to-date information.

- Here is an option for some materials to review: http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/find-help-support

Advertisement -

3Find a quiet place and time. Have in mind a private and quiet spot where you can have the conversation. If you have siblings and don't want them to be a part of the conversation, think about times of the week that you are home with your parents when your siblings are away.[1]

- If you have trouble finding alone time with your parents, create it. Ask them to step aside into a quiet room in your home for a private conversation.

- If you don't have such a room, suggest that you go sit with them at a quiet park to have the conversation.

-

4Breathe deeply. Before you have the conversation, try to calm yourself down. You may find yourself getting nervous before such a serious conversation with your parents. Breathe in through your mouth for five seconds, holding your breath for a few seconds, and then exhale through your nose for six or more seconds.[2]

- Repeat this process until you find yourself to be in a calm and relaxed state.

-

5Tell a friend. If you have a friend who has gone through a similar situation, or who has had a difficult conversation with their parents, try asking them for advice or social support. At the least it may help reduce stress;[3] at best you will gain some insight into how serious conversations between parents and children go.

- Keep in mind, however, that the dynamic between parent and child may vary greatly across different families.

Having the Conversation

-

1Tell them what you need. Say you need to tell them something important and tell them what you hope to get from them from the conversation. There are a number of things that you might want:[4]

- If you just want them to listen and offer emotional support, let them know that.

- If you want their advice, let them know.

- If you need their financial support, e.g., to see a mental health professional, mention that.

-

2Start broad. You need to let them know that you want to have a serious conversation in private. This means starting the conversation in a general kind of way that conveys that you have a problem you want to discuss without getting into the specifics just yet. Here are some examples of broad conversation starters:[5]

- "I have a problem that I need to tell you about. Can we go somewhere private to talk?"

- "I could really use your advice on an issue I'm having. Can we go for a walk?"

- "I really need your help with something private; I want to talk to you alone about it."

-

3Keep your parents' perspective in mind. Try to remember that they may not know certain things about you, or that they may see the world a bit differently than you do. As you have the conversation, try to keep their perspectives in mind to ensure that you are all on the same page.[6]

- As you are explaining things, keep track of their faces. If either parent looks confused, ask them if anything you said is unclear.

-

4Update them on what you know. Make sure you tell your parents all the information that you have about your eating disorder. Do you suspect that you have an eating disorder but have never been diagnosed by a mental health professional? There are also many kinds of eating disorders that are treated differently and that can have different negative effects on your health. This is all information your parents should know. Be sure to describe if you have:[7]

- Anorexia nervosa, which involves an inadequate consumption of food leading to low body weight.

- Binge eating disorder, which involves recurrent episodes of eating large quantities of food.

- Bulimia nervosa, which involves recurrent episodes of eating large quantities of food followed by behaviors that are intended to reduce weight gain, such as vomiting.

- Eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS).

- This may include, for example, night eating syndrome (eating excessively at night), purging disorder (purging without first binge eating), or atypical anorexia nervosa (in which weight is within the normal range).

-

5Give them time to absorb and to ask basic questions. Once you have pulled your parents aside and disclosed to them that you have an eating disorder, allow them to ask you some questions. Answer as best as you can, and be honest with them.[8]

- If you don't know the answer to one of their questions, it's fine to say that you don't know.

- If you don't want to answer one of their questions, tell them this. However, keep in mind that you parents love you and want to help. If what they are asking is relevant to your eating disorder, think carefully about your decision to not answer.

-

6Tell them your plan of action. Once you have had the conversation with them, remind them what your goals are and what you need from your parents to accomplish your goals. This could be a stay in an eating disorder clinic or to get mental health counseling.

- If you aren't sure what your goals are, or if you just wanted to express your feelings to your parents, ask them for advice. It can't hurt, and most parents love to give their children advice.

-

7Give them reading materials. If you prepared reading materials for them before having the conversation, pass them out to your parents. Give them some time to read the materials. Before parting ways, however, setup another time to meet with them for after they have read up on your specific eating disorder.

- Make sure not to overwhelm them with too many materials or with material that is not relevant to your specific eating disorder.

-

8Avoid whining or arguing. Sometimes the conversation could get emotionally rocky. You may feel that your parents aren't being as understanding as you'd hoped for, or that they don't believe you, or that they don't recognize that eating disorders are very real and serious medical disorders. Despite any of the scenarios, try to keep the conversation mature and adult-like, as anything besides that won't get you very far toward getting the help you need. [9]

- If you find your parents are not understanding you or that you are getting upset for whatever reason, consider trying to have the conversation again at a later time when you are not as upset.

-

9Mention they are not to blame. There is a chance that your parents will view your disorder as their fault. However, it is important to keep the conversation on track, either by them offering you the emotional support that you need, or by offering advice, or by getting you into treatment.

Warnings

- Eating disorders are very serious! Alert your parents or someone else who can care for you as soon as possible.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ http://kidshealth.org/kid/feeling/thought/talk_parents.html#

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/relaxation-technique/art-20045368?pg=2

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/social-support/art-20044445

- ↑ http://kidshealth.org/kid/feeling/thought/talk_parents.html#

- ↑ http://kidshealth.org/kid/feeling/thought/talk_parents.html#

- ↑ http://kidshealth.org/kid/feeling/thought/talk_parents.html#

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/warning-signs-and-symptoms

- ↑ http://kidshealth.org/kid/feeling/thought/talk_parents.html#

- ↑ http://kidshealth.org/kid/feeling/thought/talk_parents.html#