This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD. Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

This article has been viewed 25,480 times.

Narrative writing is fun to teach, but it can also be a challenge! Whether you need to teach college or grade school students, there are lots of great options for lessons. Start by getting your students familiar with the genre, then use in-class activities to help them practice creating their own narratives. Once your students understand how narratives work, assign a narrative essay for students to demonstrate and hone their skills.

Steps

Introducing the Genre

-

1Teach that a narrative has characters, conflict, and a solution. A narrative is a story, or a series of events told in a sequence. Narratives feature a character or characters who face a conflict and must work to find a solution. A narrative may be fiction or non-fiction.[1] Other features of a narrative may include:[2]

- A specific point-of-view on the events of the story

- Vivid details that incorporate all 5 senses (sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste)

- Dialogue

- A reflection on what the experience meant

-

2Assign model essays, videos, and podcasts. Giving students examples of narratives to read, watch, and listen to will help them to understand the genre better. Choose narrative models that are age-appropriate for your students. Read, watch, and listen to models in class and have students read some on their own.[3] Comic strips are also good models of narrative structure.[4]

- Have your students read narrative essays, such as "My Indian Education" by Sherman Alexie, "Shooting an Elephant" by George Orwell, "Learning to Read" by Malcolm X, or "Fish Cheeks" by Amy Tan.

- Show your students a movie, such as Moana or Frozen and then plot out the structure of the story with your students.

- Have your students listen to a podcast or radio segment that features a short narrative, such as the Modern Love podcast or NPR's "This I Believe" series.[5]

Tip

If you want to show a film but you are short on time, show a short film or sketch comedy clip, such as something from a channel you like on Youtube. Choose something that will grab your students' attention!

Advertisement -

3Discuss models in class to identify the features of narratives. Your students will need guidance as they look at models of narrative, so set aside 1 or 2 class sessions to discuss model narratives. Ask students questions to help them better understand what makes these models good examples of narrative. Some questions you might ask your students include:[6]

- Who are the characters in this story? What are they like? How can you tell?

- Who is telling the story?

- What happens to the characters?

- How do they work towards a solution to the problem?

- Where and when does the story take place?

- What is the mood of the story?

-

4Map out the plot and characters in model essays. Another way to help students see the progression of a narrative is to draw it out on a chalkboard or whiteboard. Start with what happens in the beginning of the story and move through the story paragraph by paragraph to map it out. Ask students questions as you go and encourage them to help you create the map.[7]

- For example, start by looking at the action and characters in the introduction. How does the author introduce the story? The characters?

- Then, move to the body paragraphs to identify how the story develops. What happens? Who does it happen to? How do the characters respond?

- Finish your map by looking at the conclusion to the story. How is the conflict resolved? What effect does this resolution have on the characters in the story?

Using In-Class Activities

-

1Ask students to contribute a word or sentence to a story. Telling a story 1 word or 1 sentence at a time is a fun way to help students understand the basic meaning of a narrative. Start a story that your students can build onto by saying 1 word, and then going around the room and having each student contribute a word. After doing this exercise successfully a couple of times, have each student contribute a sentence instead.[8]

- For example, you might start the story by saying “Once,” which another student might follow with “upon,” another with “a,” and another with “time,” and so on.

- You might also give the story more structure by giving your students a model to follow. For example, you might require them to follow a format, such as this one: "The-adjective-noun-adverb-verb-the-adjective-noun." Post the format where all of the students can follow along as they tell their story.

- To build a story sentence by sentence, you might start with “Once upon a time, there was a princess named Jezebel.” And then the next student might add, “She was betrothed to a foreign prince, but she did not want to get married.” And another might add, “One her wedding day, she fled the country.”

-

2Have students write a paragraph and let their classmates add to it. For a more advanced way to have students collaborate on a narrative, have each student write the first paragraph of a story. Then, ask the students to pass their paragraph to the right so that their neighbor can add onto it. After the next student has added a paragraph, they would then pass the sheet of paper to the next student, and so on until 5 or 6 students have contributed a paragraph.[9]

- Allow each student about 7 to 10 minutes to write their paragraph.

- Return the stories to the student who wrote the opening paragraph so they can see how other people continued their story.

- Ask students to share how their story progressed after they passed it to their neighbor.

-

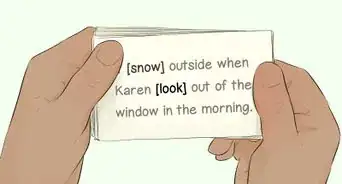

3Instruct students on showing versus telling in their stories. An important goal of narrative writing is to use dialogue and details to show readers what the characters are thinking and feeling instead of simply telling readers about these details. Explain the difference to your students by providing them with examples of what showing versus telling looks like.[10]

- For example, if the author of a story writes, “Sally was so angry,” then they are telling. However, the author would be showing by writing, “Sally slammed the car door shut and stomped off towards her house. Before she went inside, she turned, shot me a furious look, and shouted, 'I never want to see you again!'”

- The first example tells readers that Sally is angry, while the second example shows readers that Sally is angry using her actions and words.

- A great way to practice this concept is to give students a plot point or have them create their own. Then, have the students work on showing the plot point using only dialogue.

-

4Provide questions to help students develop their characters. Write and distribute a list of questions meant to help students flesh out the details of their characters. This will make it easier for them to show readers rather than telling them what the person was like. Some questions you might include in this handout might be:[11]

- What does the character look like? Hair/eye/skin color? Height/weight/age? Clothing? Other distinguishing features?

- What mannerisms does the person have? Any nervous ticks? How does their voice sound?

- What is their personality like? Is the person an optimist or pessimist?

- What are their likes/dislikes? Hobbies? Profession?

-

5Use a suspenseful opening line as a writing prompt for students. Another way to stimulate students' creativity is to ask them to write a story following an opening line that you provide. Let your students choose from a list of opening lines, and then continue the story however they want. Some examples of opening lines include:[12]

- The diner was empty, except for me, the waitress, the cook, and a lone gunman.

- I was lost in a strange city with no money, no phone, and no way to contact anyone.

- The creature disappeared as suddenly and unexpectedly as it had arrived.

-

6Have students create an island and write as if they were stranded. To give students some practice with world-building and writing from the first-person perspective, have them create an imaginary island. They can draw the island and write a description of the island's features. Then, have the students write 5 diary entries over the course of 5 days as if they were stranded on the island.[13]

- Invite students to share what happened on their islands at the end of the 5 days.

- Display the island drawings and descriptions on the wall of your classroom.

Tip

Make it your goal to do 1 activity in class each day! This will help to ensure that your students are getting lots of exposure to what a narrative is and how it works before they write their own narratives.

Assigning a Narrative Essay

-

1Explain the assignment and invite questions. Start by telling your students what their essays should be about. Cover the main features of the assignment and be clear about what you expect from your students. Provide students with a rubric for the essay so they know exactly what you will be looking for and go over the rubric together.[14]

- Tell your students if you are using a theme or focus. For example, if you want students to write their narrative on an experience with reading or writing, then you might provide examples, such as the first novel they read and fell in love with, or the time they had to totally rewrite a paper for an English class.

- Also, include details in the rubric on the required length of the essay, special features you expect to see, and any formatting requirements.

-

2Require students to submit a pre-writing activity. Pre-writing is an essential part of the writing process, so encourage your students to do this. To ensure that your students are on the right track with their topics for the essay, ask them to submit a pre-writing activity to you, such as a freewrite, an outline, or a word cluster.[15]

- Make sure to provide students with feedback on their pre-write activities. Encourage them on what sounds like it has the most potential and steer them away from topics that seem too broad or that would not hold up well as narratives.

- For example, if a student submits a freewrite in which they discuss wanting to write about all of the English teachers they have ever had, this would be too broad and you would want to encourage them to narrow their topic, such as by writing about 1 teacher only.

-

3Encourage students to start drafting early. Drafting may come easily to some students, while others may struggle through it. Either way, it is important for students to allow lots of time to revise their work, so encourage them to start writing well before the paper is due.[16]

- For example, if the paper is due on April 1st, then students ought to start drafting at least 1 week in advance, or sooner if possible. This will help to ensure that they will have plenty of time to revise their work.

-

4Hold an in-class revision session. Revision is one of the most important parts of writing, so be sure to stress its importance to your students. Set aside at least 1 full class period to do an in-class revision workshop. Provide students with worksheets to help them revise their own papers and/or their peers' papers. Additionally, have them evaluate each others' stories using the rubric you created for the assignment. Some questions you might include on the worksheet include:[17]

- Does the story seem complete? What else could be added?

- Is the topic too narrow or too broad? Does the paper maintain its focus or is it disorganized?

- Are the introduction and conclusion effective? How might they be improved?

Tip

For a creative way to showcase your students' stories, have them to transform their essays into a different format and share it with the class! For example, your students could turn their essay into a podcast, short film, or drawing.

References

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/08/learning/lesson-plans/using-the-modern-love-podcast-to-teach-narrative-writing.html

- ↑ https://www.roanestate.edu/owl/describe.html

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/08/learning/lesson-plans/using-the-modern-love-podcast-to-teach-narrative-writing.html

- ↑ http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/comics-classroom-introduction-narrative-223.html

- ↑ https://www.ecu.edu/cs-educ/TQP/upload/tqpPersonalNarrativeAug2014.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/08/learning/lesson-plans/using-the-modern-love-podcast-to-teach-narrative-writing.html

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/08/learning/lesson-plans/using-the-modern-love-podcast-to-teach-narrative-writing.html

- ↑ https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Books/Sample/00465Chap07.pdf

- ↑ https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Books/Sample/00465Chap07.pdf

- ↑ https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Books/Sample/00465Chap07.pdf

- ↑ https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Books/Sample/00465Chap07.pdf

- ↑ https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Books/Sample/00465Chap07.pdf

- ↑ https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Books/Sample/00465Chap07.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/08/learning/lesson-plans/using-the-modern-love-podcast-to-teach-narrative-writing.html

- ↑ http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/comics-classroom-introduction-narrative-223.html

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/