wikiHow is a “wiki,” similar to Wikipedia, which means that many of our articles are co-written by multiple authors. To create this article, 13 people, some anonymous, worked to edit and improve it over time.

This article has been viewed 63,997 times.

Learn more...

Swimming in lakes, rivers, and streams can be safe at designated swimming areas that are protected by lifeguards. However, drowning is the fifth leading cause of unintentional injury and death in the U.S. [1] More skills and energy are required for natural water environments because of cold water and air temperatures, currents, waves, and other conditions—and these conditions can change due to weather. Knowing how to survive and get out of a river current can save your life - and others.

Steps

Avoiding Getting Stuck

-

1Know the risks of swimming in rivers. Swimming is a hazardous activity, even for people who are strong swimmers. Areas which are not monitored or designated for swimming are much more so. Even though swimming in a river on a hot day is a great pleasure, very often there are not the safeguards one would find at a pool or a lifeguard protected beach.

- Humans do not swim well. Humans are not well-designed for swimming. An Olympic-class athlete can swim about 4.5 m.p.h, or about 2 meters a second. The average swimmer swims much slower than that. It does't take too strong a current to overcome a swimmer's abilities.

- Most drownings take place in outdoor water bodies.[2]

-

2Know the dangers of currents. Rivers are natural features, which are often inconstant and change from day to day, season to season. Rivers may have very fast currents, and getting caught in rushing water can be very dangerous. Also, it is not always easy or obvious that a waterway has a strong current. Check for:

- Weather. If it has been raining heavily, chances are good that the water level is up.

- "Flash flood" prone areas. Some rivers are noted for suddenly flooding due to mountain rain or other geological conditions.

- Obvious fast-moving currents, waves, and rapids, even in shallow water.

- Hazards, such as dams, underwater obstacles, or rocks or debris moving on the surface or along the bottom of the water.

Advertisement -

3Try to determine how fast the water is moving. Throwing objects, especially buoyant objects, such as wood or a stick (Do not throw man-made items, plastic or glass) into the middle of the river will begin to give you an idea of the speed.

- Remember, there is sometimes a current on the surface, and an undercurrent. The speed on the surface will not give you an indication of the undercurrent.

- Just because the surface is slow moving does not mean it is safe. What looks like a calm river from the outside can be home to fast-moving undercurrents.

-

4Know the abilities of those going with you, including swimming abilities and level of supervision required. Be sure to provide appropriate supervision.

- Ensure everyone learns to swim well by enrolling them in age-appropriate learn-to-swim courses. However, this does not mean people are protected from mishaps. In the case of small children, it can actually make them over-confident of abilities.

- Have weak swimmers wear U.S. Coast Guard-approved life jackets whenever they are in, on or around water. Do not rely upon water wings or inflatable toys; they can enable swimmers to go beyond their ability or suddenly deflate, which could lead to a drowning situation.

-

5Practice normal swim safety.

- Always swim with a buddy. Never swim alone, or with someone who cannot swim.

- Always enter unknown or shallow water cautiously, feet first.

- Dive safely. Diving areas should be at least 9 feet deep with no underwater obstacles. Rivers typically rise and lower in height, and the riverbed may shift--it is usually not possible to know if it is truly safe for diving.

- Do not jump from a great height, such as a tree, ledge or bridge.

- Be careful when standing to prevent being knocked over by currents or waves.

- Do not use alcohol and/or drugs before or while swimming, diving or supervising swimmers.

Getting Out of a Current

-

1Do not panic or flail. As with a riptide, panicking and flailing your limbs can push you deeper into the water. Try to take even breaths and remain calm. Hyperventilating and panicking can cause you to become exhausted and go under. Breathing in can cause you to be more buoyant, helping to reduce sinking.

-

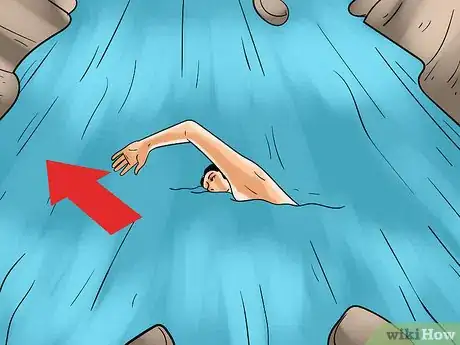

2Aim to swim diagonally toward the shoreline. Do not try to swim straight towards the shore, as you will fight with the current too much and waste energy. Try to swim at a 45° angle; you will move down further than if you were swimming without a current.

-

3Do not try to swim upstream. It will not work. If you are swept away you are already in current too strong for you to overcome that way.

-

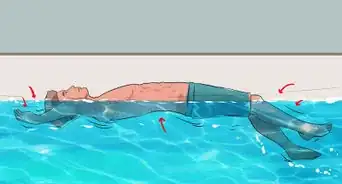

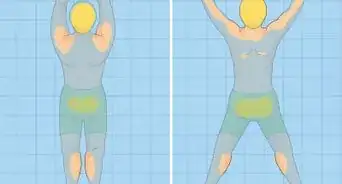

4Float down on your back, with your feet pointed downstream, and your head positioned upstream. This is the way most experts recommend. [3] This way, your head is protected. Your legs and feet will take any of the damage from rocks and debris. The top half of your feet should be poking out of the water, flexed, and your head should be above water as well. Look downstream and keep calm, and breathe with the flow of the water, to keep from swallowing too much water. When you come upon a calmer area, flip over and swim diagonally toward shore, with the flow of the current.

-

5Call for help. Make as much noise and draw as much attention as you can. With this, would-be rescuers can not only keep you above the water, but also pull you back in.

- It's helpful to bring a life buoy (a.k.a a ring buoy). This way, you can both stay above the water, and get pulled back in.

- Don't expend too much energy while calling for help. Splashing is rarely heard in rapids or from a distance, so try not to splash water unless you have spotted someone nearby and are trying to draw their attention.

-

6Get medical help. Chances are good that you will be absolutely fine, but an incident like this needs a medical examination. Usually, a 911 (emergency) call will summon paramedics and EMT.

- Long periods in cool or cold water put you at risk of hypothermia and frostbite.

- You may have ingested a large amount of water, especially if you became panicky.

- You may be in shock, psychologically or physically.

- Seek medical immediately if you suspect a concussion, or other injury. Likewise if anyone is injured, or is unresponsive, call your local emergency services.