This article was co-authored by Dan Bodner. Dan Bodner is a Transitional Shelter & Homelessness Expert and the CEO & Founder of QuickHaven Transitional Shelters. With over 20 years of experience, he specializes in executive leadership, product development, and innovation, which have helped him develop modular tiny homes to improve the lives of those affected by homelessness. Dan earned a BA from Vassar College and an MS from the University of Texas at Austin.

There are 27 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 66,013 times.

Poverty is one of humanity's most intractable social problems. It will take global effort to end completely, but each individual can play a part. It won't be easy, because reducing poverty is different from helping a poor person. While poverty is a social problem, being poor is an individual problem. With knowledge, commitment, and effort you can make a difference. With your vote and your dollars, you can support policies that reduce poverty. With your voice, you can raise awareness and advocate for change. And with your effort, you can organize like-minded people to make change from the bottom up.

Steps

Supporting Effective Poverty Reducing Programs

-

1Support quality education for all. On an individual level, the extent of a person's education is one of the strongest predictors of income potential. So by supporting programs that strengthen the educational system, you help give individuals the tools they need to stay out of poverty.[1]

- Education is multidimensional. A good education results from a combination of factors, including the skill of the instructors, funding for educational supplies (like textbooks or computers), and diligent attention to performance in every grade level. So when you want to support quality education, it means supporting a variety of programs—from training of the instructors to equal access—that help students maximize their academic potential.[2]

- While a good education makes it less likely that a child will grow up to be a poor person, it doesn't eliminate poverty itself. Poverty is simply a lack of resources (money, in the modern economy). If everyone has resources, no one will be poor. Education doesn't directly address that problem. If everyone got a medical degree tomorrow, the world would still need janitors, cashiers, and fruit pickers—and they still wouldn't make much money.

-

2Make sure people are paid fairly. The two simplest ways to do this include setting minimum wage levels that keep people out of poverty, and enforcing robust collective bargaining and unionization policies, such as a guaranteed right to strike, protections against retaliation, and automatic union registration.[3]

- While many economists believe that minimum wages increase unemployment, the evidence for this is weak.[4]

- Perhaps the best evidence for a high minimum wage is this: not a single rich country has a low minimum wage, and not a single poor country has a high minimum wage. Although there are a few European countries with no national minimum wage, trade unions negotiate minimum wage rates for each sector of the economy.[5]

- Strong unions generally mean high wages. The United States is the only rich country in the world with weak labor laws. Unsurprisingly, the US has the highest poverty rate of all rich countries, and one of the lowest rates of unionization. As the share of the unionized workforce has declined, the rise of working poverty has increased in tandem.[6]

Advertisement -

3Increase the social safety net. While education and strong wages prevent people from falling into poverty in the first place, the social safety net safeguards those who do fall into poverty. The social safety net includes cash transfers, in-kind benefits, and statutes defining the duties of creditors to debtors and employers to employees. The stronger the social safety net, the farther it pulls people out of poverty. Social safety net benefits in the US are often insufficient to pull someone all the way out of poverty, meaning that even with their eligible benefits factored in, they still fall below the poverty line.[7]

- The classic example of US cash transfer programs are Social Security Disability (SSD) benefits and Supplemental Security Insurance (SSI). SSI, for example, simply gives certain types of poor people money—a cash transfer from the government to the individual.[8]

- SNAP (food stamp) benefits and Medicaid are in-kind benefits. These programs don't give a person money so that they can get their own food and health care, they give them the good or service directly.

- Statutes contributing to the social safety net might include usury laws, which define the maximum allowable interest a person can be charged, bankruptcy protection, and paid sick leave laws.[9]

-

4Broaden ownership. The ownership of assets determines wealth, while the amount of money a person makes determines income. Most poverty reduction programs emphasize increasing incomes, but increasing wealth is just as important, because wealth is more permanent. Broadening ownership can be accomplished in many ways, including:

- Increasing access to low interest credit for poor people.[10] Interest is the price of money. If money is lent at a low price, it allows people to buy assets, like real estate or businesses, at a low price.[11]

- Creating strong legal incentives for employee ownership.[12] Giving employees ownership of the firms they work for broadens the distribution of assets. For example, firms over a certain size might be required to divest stock to their employees in proportion to the profit derived from their labor—imagine the how differently wealth might be distributed if the employees of a huge corporation like Walmart were all stockholders in the company.

- Take a house as a metaphor for wealth and income. The construction crew that builds the house represents income, and the building materials represent the beginnings of wealth. The crew is a valuable resource, but its benefits are transient. As long as the crew is used to build the house, the building materials have a permanent benefit.

Being an Effective Advocate

-

1Talk to your friends and associates as practice for more serious advocacy. Approach your friends, family, and acquaintances about issues you're passionate about. Your goal should be to make them care about that issue. Think about their experiences, sympathies, and temperaments so you can craft an appeal that's most likely to succeed.[13]

- For example, imagine your uncle is a police officer in a poor area. The issue you care about is education. If you want to get him to care about education in the same way you do, talk to him about how lack of educational opportunities contributes to crime. You could open by saying something like this: “You know they just cut funding for afterschool programs in Sandtown? Better get ready to start chasing kids all over the city. Kids with nothing to do get in trouble.”

- It's easier to influence someone's opinion about a new subject than it is to change their mind about something. Talk with them about unfamiliar subjects or approach new subjects in unfamiliar ways.

-

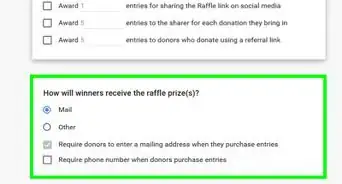

2Take advantage of social media. Social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook can be a great way to raise awareness of an issue. These tools allow you to reach large audiences with relatively little effort, and numerous issues have gone viral (achieved notoriety quickly) with the aid of social media.[14] Use social media to promote articles, videos, and memes that tackle any one of the many facets of ending poverty.

- While the reach of social media is broad, its effect is often shallow. Even though it's a great way to spread a message, social media alone usually doesn't produce lasting change. Over-reliance on social media risks creating a lot of “slacktivists,” or people who are constantly hitting the “share” button to spread a message, but take no action beyond that.[15]

-

3Become a content creator. If you want to take your advocacy one step further, create content that tackles issues relating to poverty. “Content creation” is a broad term, but all it really means is creating any type of media—whether it's audio, video, visual, or written. In order to publish your content, you can create your own platform or contribute to someone else's, depending on the effort you can devote to it.[16]

- Podcasts, blogs, and YouTube are all great ways to publish your message. You can create your own blog, podcast, or YouTube channel if you think you can attract an audience and you want complete control over messaging. See Start Your Own Podcast and Start a Blog to learn more.

- There are a lot of ways to publish your content on someone else's site but they're all going to boil down to two basic methods:[17] You can give them what they want, or convince them to accept what you're offering. Search the blogs, podcasts, and YouTube channels that you think would make a good platform for your message, and ask them their policies on submissions. Either they'll ask you to create something about a certain subject, or they'll want you to pitch them on something you're working on.

-

4Join a group. Many voices together are more powerful than one voice alone. By joining a group that's concerned with the same issues you're concerned with, you'll gain credibility and access.

- For instance, if your particular concern is poverty among working women, you can join a group like 9 to 5, which lobbies and advocates on that particular issue.[18] As a member of 9 to 5, you'll gain credibility when you talk to others about poverty among working women. Saying, “I'm a member of 9 to 5, and we lobby and organize on behalf of issues of special concern to poor and working women,” has a much better ring to it than “You know what I think?”

- Plus, 9 to 5 already has a newsletter, a website, and a blog. What better way to spread your ideas about poverty and working women than broadcasting them to a group you already know cares about that issue?

-

5Reach out to the decision makers. Be an advocate by taking your message to people who have the power to make the changes you want to make. With a problem as big as poverty, there are a lot of decision makers and a lot of ways to communicate with them. For example:

- You can write a letter to the editor of your local newspaper, your congressman, senator, mayor, or other political figure.

- Call your elected representative (or a local politician, like a city administrator or city council member)

- Start an online petition (that you spread through social media). Since one voice might not be enough, let the decision makers know just how many people care about the issue you're passionate about.

- Change.org is one of the best known places to create an online petition, but it's far from the only one.[19]

- If you gather enough signatures, invest the money and time in printing out a hard copy. Hand delivering a stack of papers with 30,000 signatures is more visually impressive than sending an email with an attachment.

Organizing for Change

-

1Narrow down your issue. You want to reduce poverty, and that's a laudable goal. But the number of people who want to increase poverty approaches zero. So why is poverty still a problem? One reason is that poverty is a big problem, and most people don't know where to start.[20]

- So if you try to organize a group to “fight poverty,” people are going to want to know how you plan on doing it and where they fit in. Unless you can give them an answer that will make them understand how their specific action will lead to the tangible result of less poverty, it's going to be a tough sell. That's why you narrow your message.

- In the beginning, your issue should be as concrete and specific as possible. For instance, you could advocate for a homeless village in your area, explaining how it's a cost-effective way to reduce homelessness that benefits the local community.

-

2Identify your allies. Even if you have a perfect message and an ingenious strategy to solve the problem you want to solve, you need to have comrades-in-arms to execute the strategy. You'll make much better progress if you approach them than if you wait for them to approach you, so identify who those people are.[21]

- Rate your allies and enemies on a spectrum from friendliest to most hostile. Leading activists and active allies should be on one end with active and leading opponents on the other end.

- For example, if you want to make the Tiny House Project a reality, leading activists and active allies might be those that already help the homeless, like directors of soup kitchens and shelters. The leading activists will be those with a public profile, and the active allies are those that are involved in the work but have a lower profile. Leading and active opponents might be developers, members and leaders of Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) groups, and their elected officials.

-

3Work out the preliminary details of your plan. Once you've identified who is likely to be with you and against you, you need to work out the basic details of how you will accomplish your goal. You don't have to account for every cent of your budget and plan out an itinerary for every day of the next year. But you should estimate the cost, and you should project how much time it will take to hit your goal.[22]

- You're sketching your basic plan so that you can have an effective pitch when it comes time to recruit your allies. Therefore, try and work out how the success of your plan will benefit your prospective allies. So explain to the director of the shelter how many beds the Tiny House Project will free up for her shelter.[23]

-

4Develop a core group.[24] Once you've identified your allies and created a basic plan, you need to recruit a team of leaders who can execute your project. Start by approaching the leading activists and work your way back. Look for people with ties to the community who have experience in fundraising, communications, field organizing, and working with elected officials.

- Always try and “warm up” your lead before you approach a target ally. A warm lead is just a possible ally you have a personal connection with—even if it's just through a mutual acquaintance. It's always easier to persuade a warm lead than it is a cold lead—a target you have no connection to.[25]

- Face-to-face meetings are the most effective form of contact, followed by warm phone calls, warm emails, cold phone calls, and cold emails. Don't be surprised if 90% of your cold emails go unanswered.[26]

-

5Go out of your way to get input from your core group. Feedback and input is absolutely necessary, especially in the beginning stages of an issue organization. Unless you already have a legendary reputation in the activist community, people are going to want to do more than take orders from you.[27]

- Remember, you're recruiting a team from a base of allies. They wouldn't be allies if they didn't yet have ties to your cause, and they wouldn't be in the core group of activists if they didn't have the qualifications for it. Your venture will benefit from their input and contacts in unexpected ways. For instance, one of your core team members might have a connection to a dealer in discount building supplies, which could help the Tiny House venture tremendously.

-

6Build your base of support to build your power. Power is the ability to do something. You want to be able to do something, and you'll be more likely to do it if a lot of other people want to do that same thing. The most successful issue organizations have strong popular bases of support—they aren't just mailing and donor lists. If you want your organization to be successful, you need to build a base of support within the community.[28]

- Start your base building efforts by tapping the connections of those in your core team. Ideally, they recruit members and volunteers, who in turn recruit members and volunteers, and so on and so on.

- Next, connect with other sympathetic organizations. It's always best to have a connection to the organization, so if someone on your team is a member of a church, a union member, or just part of a club (like the Kiwanis, Rotary, or Lions), start there. But even if you don't have a connection to a large local church or club, you need to reach out. They can offer volunteers, possible members, and in-kind and financial assistance.[29]

- Finally engage in direct outreach to the community. Direct outreach is an activity like clipboarding at a local event, or conducting a door to door canvass. With the Tiny House Project, you could explain to them the purpose or the project and it's benefit to them (getting homeless people off the streets), and it's benefit to the recipients (creating shelter).Since these are cold leads, they're the least effective—but still worthwhile.[30]

-

7Strengthen the connections among your membership. You're building an organization to address an issue, and you'll need a strong commitment from your membership to make it happen. The best way to rally the members around the issue is to talk about it—a lot. Hold meetings open to the community and lead by your members and core leaders with the goal of raising awareness of your specific issue and coming to a consensus plan of action.

- The number one rule of a meeting is to start on time and end early. The second rule is to have a structured discussion—not aimless debate. This isn't a college bull session; whether or not the attendees know it, you're building a plan of action. [31]

- One way to apply this to the Tiny House example might be to hold a meeting related to advancing the goal--like clearing a lot to prepare it for the start of construction.

-

8Listen to what the stakeholders have to say. While you want to foster connections between the group during your meeting sessions, that's not the only use for them. You and your team need to listen to what the membership and the community have to say about the problem, how it affects them, and what a successful resolution to the problem means to them.

- Going back to the Tiny House Project example, you might have a lot of homeless and former homeless who attend your meetings. Obviously they'll want a home, but what if you hear feedback about how they want work as well? Use the feedback to your advantage—if you can have the homeless provide all or some of the labor for the construction of the houses, it can help your budget, their lives, and the local economy.

-

9Pick a fight you can win. If the powerful had the intention of solving the problem you're organizing around, it would have been solved already. But no one with power is going to listen to your requests (or demands) unless you show you have the power to complicate their lives. The pain of saying “no” to you has to outweigh the pain of saying “yes.”[32]

- Since power is the ability to do a thing, you need to demonstrate your organization's ability to do things. Don't undermine the perception of your power by picking a fight you're sure to lose.

- For example, you probably don't want to try and storm City Hall for your very first demonstration of power, because City Hall is an intimidating and well defended target. However, if the local developers are the ones standing in the way of the Tiny House Project, you can probably execute a very disruptive (but peaceful) demonstration at the local Chamber of Commerce Picnic. A demonstration of that type grabs a lot of attention, which generates notoriety, which generates membership, which further increases your power.

-

10Rehearse, then execute. Practice makes perfect. Before you launch your demonstration, make sure that everyone knows their roles and tasks. Make sure the demonstrators know what to do in the event that law enforcement makes an appearance or the crowd where they are demonstrating turns hostile.

- A lot of people think role-playing is kind of cheesy, and they're right. Nonetheless, role-playing is one of the most effective ways to prepare people for the anger of a hostile crowd.

-

11Up the ante until your opponent folds. A successful demonstration of power can begin a positive feedback loop. The success increases your power, which should allow you to pick a more significant target. You need to keep picking fights you can win until your opponent gives in.[33]

- For example, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s was kickstarted by the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The municipal bus system of a small Southern town is a relatively minor target, but the success of the Boycott strengthened the Movement. The Movement went on to target progressively larger targets, like Woolworth's, the state of Mississippi, and the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Your Tiny House Project probably won't require quite as big of an effort, but the same principle applies.

Community Q&A

-

QuestionWhat causes poverty?

Community AnswerAll sorts of things cause poverty, but at it's basically a problem of insufficiency. Some people have too much and some people have too little.

Community AnswerAll sorts of things cause poverty, but at it's basically a problem of insufficiency. Some people have too much and some people have too little.

References

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/11/business/economy/a-simple-equation-more-education-more-income.html

- ↑ http://www.ncee.org/programs-affiliates/center-on-international-education-benchmarking/top-performing-countries/

- ↑ http://www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/survey_ra_2014_eng_v2.pdf

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/01/04/economists-agree-raising-the-minimum-wage-reduces-poverty/

- ↑ http://www.wageindicator.org/main/salary/minimum-wage

- ↑ http://asr.sagepub.com/content/78/5/872.full.pdf+html

- ↑ https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/naldc/download.xhtml?id=AGE86927832&content=PDF

- ↑ https://www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-05-11069.pdf

- ↑ https://americansforfairnessinlending.wordpress.com/the-history-of-usury/

- ↑ https://publicpolicy.stanford.edu/publications/access-credit-viable-means-poverty-alleviation-0

- ↑ http://www.grips.ac.jp/vietnam/VDFTokyo/Doc/1stConf18Jun05/OPP01QuachPPR.pdf

- ↑ file:///C:/Users/Devan/Downloads/All-2008-University_of_Pennsylvania_Journal_of_Business_and_Employment_Law-Varieties_of_Employee_Ownership.pdf,

- ↑ http://www.forbes.com/sites/ashoka/2014/09/25/how-to-use-muscular-empathy-to-drive-social-change/

- ↑ http://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/AFC_Manual_01.pdf

- ↑ https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/04/unicef-tells-slacktivists-give-money-not-facebook-likes/275429/

- ↑ https://advox.globalvoices.org/wp-content/downloads/gv_blog_advocacy2.pdf

- ↑ http://webwriterspotlight.com/how-to-pitch-stories-to-major-web-publications

- ↑ http://9to5.org/home/

- ↑ https://www.change.org/start-a-petition

- ↑ https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/communications-campaign-best-practices.pdf

- ↑ http://organizingforpower.org/resources-for-ally-coalition-building/

- ↑ https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/communications-campaign-best-practices.pdf

- ↑ http://organizingforpower.org//wp-content/uploads/2009/06/building-alliances-guidebook.pdf

- ↑ http://organizingforpower.org//wp-content/uploads/2009/06/building-alliances-guidebook.pdf

- ↑ http://www.investopedia.com/terms/w/warm-calling.asp

- ↑ http://isps.yale.edu/node/16698

- ↑ http://organizingforpower.org//wp-content/uploads/2009/06/building-alliances-guidebook.pdf

- ↑ http://organizingforpower.org/people-power-2/

- ↑ http://organizingforpower.org//wp-content/uploads/2009/06/building-alliances-guidebook.pdf

- ↑ http://organizingchange.org/how-to-expand-on-these-4-community-organizing-fundamentals/

- ↑ http://organizingforpower.org//wp-content/uploads/2009/06/building-alliances-guidebook.pdf

- ↑ http://beautifultrouble.org/principle/choose-your-target-wisely/

- ↑ http://beautifultrouble.org/principle/choose-your-target-wisely/