This article was medically reviewed by Luba Lee, FNP-BC, MS. Luba Lee, FNP-BC is a Board-Certified Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP) and educator in Tennessee with over a decade of clinical experience. Luba has certifications in Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), Emergency Medicine, Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Team Building, and Critical Care Nursing. She received her Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) from the University of Tennessee in 2006.

There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 82,106 times.

The brachial pulse is commonly taken when you check blood pressure. It’s also the easiest way to check for a pulse in infants. Taking the brachial pulse is no different from checking the pulse in your wrist or neck. It just takes some practice feeling around your inner arm for the beat of the brachial artery.

Steps

Locating the Brachial Artery

-

1Extend an arm and tilt it so that your inner elbow faces upward. Relax your arm and bend it very slightly at the elbow. It doesn’t need to be rigid. You should be able to see and easily reach the crease of the elbow, also known as the cubital fossa.[1]

-

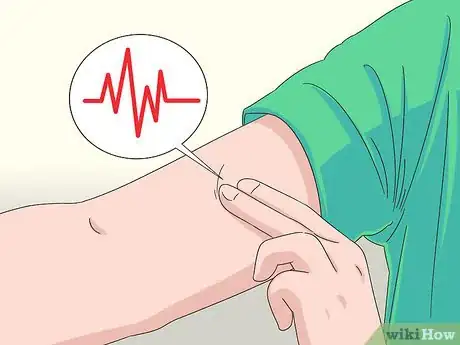

2Place 2 fingers on your upper arm just above the cubital fossa. Feel around in the area just above the crease of the elbow. You should feel a slight indent in between the bicep and your brachialis muscles, which is right above the inside of your elbow. These muscles should meet at about the midpoint of the cubital fossa.[2]

- Use your index and middle fingers, if possible. These fingers will have the easiest time feeling for the pulse. Do not use your thumb, as it has its own pulse that may confuse your readings.

- You should be able to see the brachial artery on your inner arm.

Advertisement -

3Hold your fingers still to feel for a beat. The pulse indicates that you’ve found the brachial artery. The beats will be slight, similar to the pulse on your wrist or neck.[3]

- If you’ve never taken a pulse before, feel for your pulse on your neck. This is where a pulse is generally easiest to feel. It should be detectable on either side of your throat. This gives you an idea of the beat you should feel in the arm.

-

4Adjust your fingers if you don’t feel the beat. If you can’t feel the pulse, try pressing a little harder into your arm. The brachial artery is deep in the muscle, so it can take some gentle pressure to feel. If you still can’t find the pulse, move your fingers around in the cubital fossa until you feel a thump.[4]

- The pressure should be gentle and light. If you or whomever you’re checking the pulse of feels any discomfort from the pressure of your fingers, you’re pushing too hard.

Measuring Your Pulse

-

1Count the beats you feel for 15 seconds to get a quick pulse. Make sure you time yourself to get an accurate reading. It helps to use a watch, clock, or the timer on your phone so that you aren’t trying to count time and the pulse at the same time.[5]

-

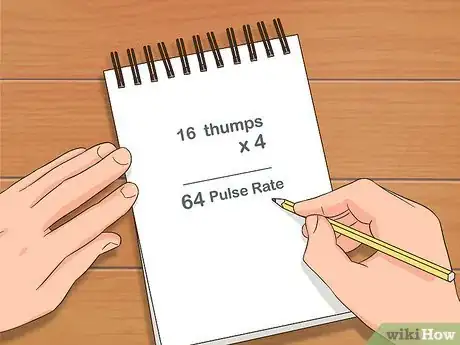

2Multiply your 15-second count by 4. The pulse measures the number of times your heart beats in a minute. To get a full minute, then, you need to multiply the number of thumps you felt during your 15-second check by 4. This gives you the count of your full, 60-second pulse.[6]

- So, for example, if you felt 16 beats when you checked the pulse, you would multiply that by 4 to get a pulse rate of 64 beats per minute.

-

3Check the pulse for a full 60 seconds for the most accurate reading. Taking the pulse for 15 seconds gives you a good estimate of the overall pulse rate. Measuring the pulse for a full 60 seconds, though, gives you the most accurate reading since you can feel the strength and regularity of the beats. Use a clock, stopwatch, or timer to count the number of beats from the brachial artery for a full 60 seconds.[7]

- Taking the brachial pulse for a full 60 seconds allows you to feel things like skipped beats or arrhythmic beats that may not come through in a 15-second check. Use a 60-second reading for heart patients or anyone in shock.

- You can also get a more accurate reading by repeating the 15-second count a few times, then finding the average of the readings.[8]

Checking the Brachial Pulse in Infants

-

1Place the infant on their back with one arm flat along their side. The crease of the elbow should be facing up so that you can access it without having to move the baby. Do this at a time when the baby isn’t fussy or moving around too much, if possible, so that you can get the best reading.[9]

-

2Place 2 fingers just above the elbow crease and feel for a beat. Gently move your index and middle finger around the baby’s upper arm in the area just above the cubital fossa until you feel a beat. The beat will be very light, so work slowly to make sure you don’t miss it.[10]

-

3Compress your fingers gently to get a pulse reading. Once you think you’ve found the brachial artery area, compress your fingers slightly so that you can feel the full pulse. You should be compressing enough to just barely indent the baby’s skin.[11]

- Finding the pulse on an infant is difficult to do. Try to be free of distractions and only focus on the beats.

- If you’re unsure of how hard to press, ask your pediatrician next time you take your baby in for an appointment. They can show you how to properly check for a pulse.

-

4Measure the pulse for 10-15 seconds if you need a pulse rate. Often, when you check a baby’s pulse, you’re just checking to make sure a heartbeat is present. If you’re taking their pulse rate, though, use a clock, watch, or timer and count the number of beats you feel for no more than 10 seconds.[12]

- If it’s not an emergency, you can take your time and do a longer reading (e.g., 30 seconds).[13]

-

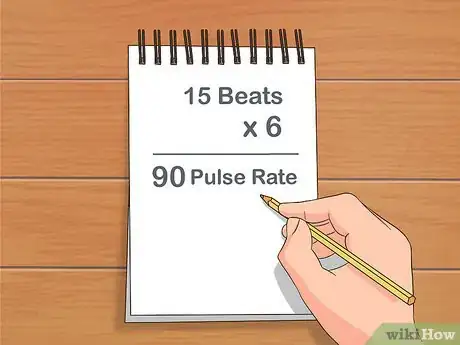

5Multiply your count to get a 60-second pulse. If you measured the pulse for 10 seconds, multiply your count by 6. If you measured the pulse for 15 seconds, multiply your count by 4. This will give you the approximate beats per minute.[14]

- For example, if you counted 15 beats in 10 seconds, you would multiply 15 by 6 to get a pulse rate of 90.

- If you counted 21 beats in 15 seconds, you would multiply 21 by 4 to get a pulse rate of 84.

Warnings

- If you cannot find a pulse, make sure the person is conscious or breathing by trying to rouse them awake.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nursing/Book%3A_Vital_Sign_Measurement_Across_the_Lifespan_(Lapum_et_al.)/03%3A_Pulse_and_Respiration/3.20%3A_Brachial_Pulse

- ↑ https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes3/manuals/pressure.pdf

- ↑ https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes3/manuals/pressure.pdf

- ↑ https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes3/manuals/pressure.pdf

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/Nemours/en/parents/take-pulse.html

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/Nemours/en/parents/take-pulse.html

- ↑ https://www.mayoclinic.org/how-to-take-pulse/art-20482581

- ↑ https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/want-to-check-your-heart-rate-heres-how

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/take-pulse.html

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/take-pulse.html

- ↑ https://www.nationalcprassociation.com/infant-pediatric-cpr-study-guide/

- ↑ https://www.redcross.org/content/dam/redcross/atg/PHSS_UX_Content/CPRO_Handbook.pdf

- ↑ https://www.hopkinsallchildrens.org/Patients-Families/Health-Library/HealthDocNew/How-to-Take-Your-Child-s-Pulse

- ↑ https://www.nationalcprassociation.com/infant-pediatric-cpr-study-guide/

- ↑ https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003399.htm

-Step-3-Version-3.webp)

-Step-3-Version-3.webp)

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...