This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD. Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 98% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 64,580 times.

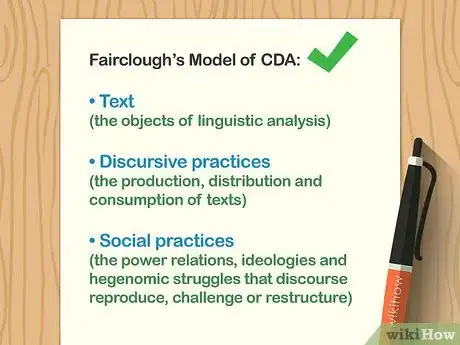

The field of critical discourse analysis (CDA) involves taking a deeper, qualitative look at different types of texts, whether in advertising, literature, or journalism. Analysts try to understand ways in which language connects to social, cultural, and political power structures. As understood by CDA, all forms of language and types of writing or imagery can convey and shape cultural norms and social traditions. While there is no single method that covers all types of critical discourse analyses, there are some grounding steps that you can take to ensure that your CDA is well done. [1]

Steps

Working with a Text

-

1Select a specific text that you'd like to analyze. In critical discourse analysis (CDA), the term “text” has many meanings because it applies to any type of communication, whether it's words or visuals. This includes written texts (whether literary, scientific, or journalistic), speech, and images. A text can also include more than 1 of these. For example, a text could have both written language and images. According to the University of Utrecht a discourse analysis can also be conducted on items without text if you "read" how the item conveys a message. If you're working on CDA in a college-level course, your professor may have already assigned you a text to work with. Otherwise, choose your own.[2]

- Texts could include things like Moby Dick, Citizen Kane, a cologne advertisement, a conversation between a doctor and their patient, or a piece of journalism describing an election.

-

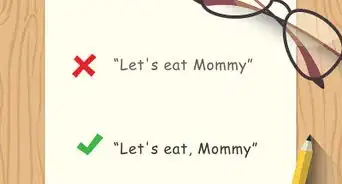

2Look for words and phrases that reveal the text's attitude to its subject. Start your CDA at the most specific level: look at the words of your chosen text. Whether it's intentional or not, word choices can show the way an author feels about the subject of the text. Ask yourself: What specific tone or attitude are these words conveying?[3]

- As a first step, circle all of the adverbs and adjectives in the text. Then, consider what they might suggest about the tone of the piece.

- Look for tone words to help you figure out what the author is trying to convey.

- For example, say you're looking at a piece of political journalism about the president. If the text describes the president as “the goofball in the Oval Office,” the attitude is sarcastic and critical.

- However, if the president is described as “the leader of the free world,” the attitude is respectful and even reverential.

- If the article simply refers to the president as “the president,” its attitude is deliberately neutral, as if the text refuses to “take sides.”

Advertisement -

3Consider how the text includes or exclude readers from a community. One of CDA's main claims is that all language is social and communicative. Texts build social communities by using specific words and phrases to help readers feel engaged and understood. Look at your text and spot a few places where it works to build a community. Identify the audience the author is addressing, and explain why you came to that conclusion.[4]

- For example, think about a news report about international immigrants coming to a country. The newscaster can create different types of community by referring to the immigrants as “strangers,” “refugees,” or “aliens.”

- The word “refugees” will prompt sympathy among listeners and will help build a community between citizens and immigrants, while “alien” will help create hostile feelings and will exclude the immigrants from the nation's community.

-

4Look for assumed interpretations that the text has already made. As a critical reader, it's your job to analyze the assumptions that exist in texts that less-critical readers may overlook. Read closely to find spots where language, tone, and phrase choices reveal textual biases about its subject matter. Every text has implicit assumptions, and it's your job as a CDA analyst to identify them.[5]

- For example, an 18th century short story that begins, “The savages attacked the unarmed settlers at dawn,” contains implicit interpretations and biases about indigenous populations.

- Another story that begins, “The natives and settlers made a peaceful arrangement,” has a comparatively benign interpretation of historical events.

Analyzing the Text's Form and Production

-

1Think about the way your text has been produced. Textual production means how a text was created, which includes the historical context, cultural context, authorship, and format. This can carry a lot of meaning. In the case of literature, if a text was composed by 1 author, many of their personal views may be expressed in the text and give it a bias. If the text is a document of selected famous quotations, though, it will not show a single individual's beliefs or biases since it's been written by multiple authors.[6]

- For example, think about the difference between an author who writes a novel for money and one who writes for their own pleasure.

- The first author would want to tap into popular trends ends of the day in order to profit, while the second author would be less concerned with pleasing the public.

-

2Examine the form of the text and consider who has access to it. Within CDA, a text's form and its audience are closely related. The form of a text can be more or less accessible in ways that show who the text's creator wants to have access to the text and who they would like to remain outside of the community that the text creates.[7]

- For example, consider the case of a CEO delivering a speech in person to their company. The fact that they're delivering a speech and not sending an open letter shows that openness and transparency are important to the CEO and the company culture.

- If the CEO did not deliver a speech, but only sent an email to board members and top executives, the formal change would imply that the text had a very different audience. The email would make the CEO seem less personal, unconcerned about their own workers, and elitist in who they chose to address.

-

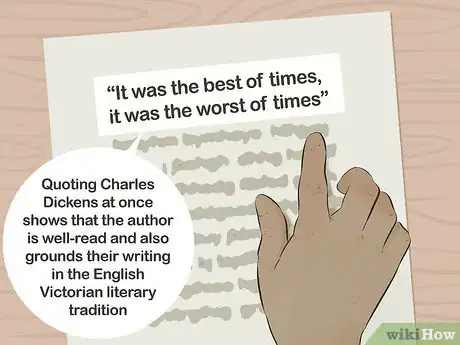

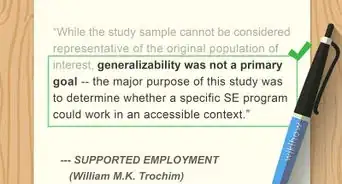

3Analyze quotations and borrowed language in your text. Think about what these quotes are doing and what the author might be trying to communicate. Texts commonly include quotes, borrow passages from other well-known texts, or pay homage to famous texts. Quotations can place a text into a certain literary or journalistic tradition, can show a reverence for history and the past, or can reveal the type of community that the text's creator would like to build.[8]

- For example, say that a contemporary writer opens a poem or story with: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” Quoting Charles Dickens at once shows that the author is well-read and also grounds their writing in the English Victorian literary tradition.

Tracing Power in Social Practices

-

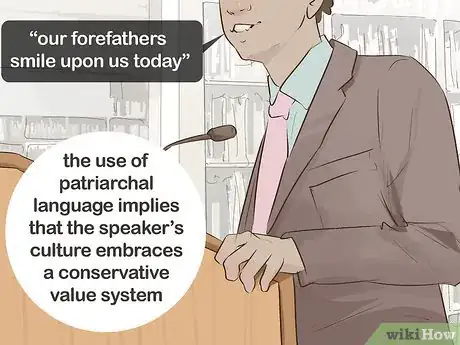

1Examine ways in which texts reveal traditions within a culture. Texts are powerful tools that can both reveal and create cultural values and traditions. As a CDA analyst, look for cultural clues within the texts that you're analyzing. A text can reveal ways in which the text's creator (or a group of people that the author is representing) feels about cultural traditions, or can shape the way a culture develops.[9]

- For example, if a political speakers says, “our forefathers smile upon us today,” they are using patriarchal language.

- The term “culture” should be taken very broadly. Businesses can have cultures, as can communities of all sizes, countries, language groups, racial groups, and even hobbyists can have specific cultures.

-

2Contrast similar texts to find differences between the social cultures. When you're doing a CDA analysis, it's productive to compare similar texts—e.g., 2 advertisements or 2 screenplays—with one another. This can lead to new understandings of the texts themselves. Comparing 2 texts can also help analysts understand differences between the social values held by different communities and cultures.[10]

- For example, consider 2 different magazine ads for trucks. In the first, a rugged-looking man sits in a truck below the words “The vehicle for men.” In the second, a family sits in a truck and the ad copy reads, “A truck to hold everybody.”

- The first ad seems to rely on stereotypical ideas of masculinity, while the second seems more inclusive.

-

3Determine whether norms are held by a culture or a sub-culture. Many large groups—including businesses and other organizations—contain many smaller sub-cultures. These sub-cultures typically have their own norms and traditions that may not be shared in the large culture as a whole. You can analyze whether a view is held in a large culture or a small sub-culture by figuring out the intended audience for the group's texts and understanding how the text is received by different groups.[11]

- For example, imagine a politician whose slogan is “All energy should come from coal!” Because of the extremity of the stance, you may suspect that the candidate represents a fringe party that doesn't share many of the mainstream party's views.

- You could confirm this suspicion by looking at other candidates' speeches to see how they address the fringe candidate. If other candidates critique the fringe candidate, the latter is likely part of a sub-group whose views aren't shared by the main political culture.

-

4Consider ways in which cultural norms may exist internationally. In a small number of cases, power grounded in texts and textual practices create such a strong culture that it crosses national boundaries. As a CDA analyst, it's your job to figure out where this type of culture exists. The effects of a strong international culture can be positive or negative. In the corporate world, for example, a shared culture could encourage tolerance and inclusivity or it could encourage exploitation and abuses of power.[12]

- For example, companies like Ikea, Emirate Airlines, and McDonald's have strong cultures and norms that exist internationally.

References

- ↑ https://www.history.ac.uk/1807commemorated/media/methods/critical.html

- ↑ https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/ed270/Luke/SAHA6.html#4

- ↑ https://study.com/academy/lesson/interpreting-literary-meaning-how-to-use-text-to-guide-your-interpretation.html

- ↑ https://www.history.ac.uk/1807commemorated/media/methods/critical.html

- ↑ https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/discourse-analysis/

- ↑ https://youtu.be/3w_5riFCMGA?t=378

- ↑ https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/discourse-analysis/

- ↑ https://youtu.be/3w_5riFCMGA?t=669

- ↑ https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/ed270/Luke/SAHA6.html#4