This article was medically reviewed by Daniel Wozniczka, MD, MPH. Dr. Wozniczka is an Internal Medicine Physician, who is focused on the intersection of medicine, economics, and policy. He has global healthcare experience in Sub Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia. He serves currently as a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Public Health Service and a Medical Officer for the Epidemic Intelligence Service in the CDC. He completed his MD at Jagiellonian University in 2014, and also holds an MBA and Masters in Public Health from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 21,586 times.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is a disorder of the digestive tract. A healthy adult pancreas produces roughly 1.5 liters (51 fluid ounces) of enzyme-rich fluids daily. These fluids help your digestive tract break down proteins, fats, and starches. When one has an exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, these digestive fluids are not being produced in sufficient quantities, which results in discomfort, inadequate digestion, and eventual weight loss.[1] To diagnose an exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, you’ll need to work closely with your doctor and undergo a series of blood and stool tests.

Steps

Watching for Symptoms of EPI

-

1Pay attention to abdominal cramps. Painful abdominal cramps are a common symptom of EPI, and can be a sign that your body is not properly producing digestive enzymes or properly absorbing nutrients. If you experience chronic abdominal pain, plan to schedule an appointment with your doctor and inquire about EPI.[2]

- EPI is particularly associated with epigastric abdominal pain, which is pain in the upper abdomen between your sternum (breast bone) and navel. This pain may radiate to your back.

- EPI is often difficult to diagnose, since its symptoms—including abdominal cramps—are shared by several other abdominal and digestive disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome, bowel inflammation, gallbladder diseases, and peptic ulcer disease.

-

2Watch out for weight loss or an inability to gain weight. Since EPI diminishes healthy digestive enzymes in your body and reduces your body’s ability to digest and absorb healthy fats and vitamins from food, it’s common for individuals with EPI to lose weight, sometimes at a rapid pace.

- As another side effect of inadequate digestion, individuals with EPI can experience frequent tiredness or fatigue.

- Inability to gain weight is a common symptom of EPI in children. Since children weigh relatively little to begin with, an inability to gain weight should be taken seriously when first noticed.[3]

Advertisement -

3Monitor your stools. Since EPI is a condition of the digestive system, it can have a significant on the frequency and consistency of stool. Nearly all individuals with EPI suffer from diarrhea, which in the case of EPI is known as “steatohhrea.” This stool characterized as greasy, bulky, pale, watery, and very foul-smelling.

- Steatohhrea is higher in fats than healthy stool, since EPI prevents the body from fully digesting all of the fats that would normally be absorbed into the bloodstream. This condition puts you at high risk for losing important fat-soluble vitamins, like vitamins A, D, E and K, and may result in vitamin deficiencies.[4]

- The stool may contain oily droplets, and may float to the surface of the water in the toilet bowl, making it difficult to flush at times.

Testing Blood and Stool to Diagnose EPI

-

1Ask your doctor about blood work. Blood testing is a common initial step in testing for EPI, although the blood-test results can only confirm problems symptomatic of EPI; results from bloodwork alone cannot be used to fully diagnose EPI.

When your blood is submitted to a lab, its red-blood count will be determined, since anemia (low red-blood cell count) is a common condition in patients suffering from EPI.[5]

The lab work will also test your blood for an unusually high presence of nutrients that would usually be absorbed by a body producing healthy levels of pancreatic enzymes. These nutrients include iron, vitamin B12, and folate. -

2Give a stool sample for a fecal elastase test. Since the digestive tract is the bodily system most effected by EPI, evaluating a stool sample is an effective way to gauge a body’s digestive health.

For an elastase test, you’ll need to provide your doctor with a single solid stool sample, which will be sent to a lab and evaluated for an enzyme known as “elastase.”[6]- This enzyme plays an important role in breaking down food during the digestive process. Individuals with EPI tend to have uncommonly low levels of elastase.

-

3Give a stool sample for a 3-day fecal test. In addition (or instead of) the stool sample for the elastase test, your physician may ask you to provide a stool sample for a 3-day fecal test. To produce the required sample, collect samples of your stool over a 3-day period and deliver them to your doctor.

Similar to a fecal elastase test, a 3-day test will also be sent to a lab, where the amount of fat that the stool contains will be tested.[7]- Excessively fatty stool is a sign of EPI, since it indicates that the digestive tract is not adequately absorbing fat from digested foods, and consequently that enzymes produced in the pancreas are not present in normal quantities.

Undergoing Medical Tests for EPI

-

1Ask your doctor for a direct pancreatic function test. This is one of the most accurate means of testing for EPI. In a function test, a small needle is inserted directly into your small intestine and used to withdraw pancreatic enzyme secretions. These fluids are then tested to determine if they contain healthy or unhealthy levels of enzymes.[8]

- Despite its efficiency, this test is relatively limited and is only performed at certain medical centers or labs.

- If your primary care physician is unable to perform a direct pancreatic function test, ask if they can refer you to a nearby clinic that can do the test.

-

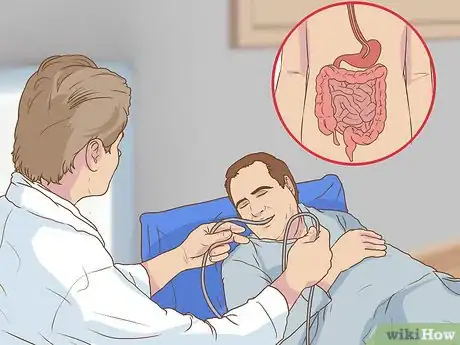

2Undergo an endoscopic ultrasound. An endoscopic ultrasound will allow your doctor to look at your pancreas itself (and other internal organs) to see if internal damage or inflammation is causing EPI or EPI-like symptoms.

This test will likely need to be given in a hospital: a doctor will snake a thin, specialized tube down your throat, through your stomach, and into the top of your small intestine.

The tip of the specialized tube will contain an ultrasound probe that produces sound waves and will produce an image of your internal abdomen, which will help doctors tell if your pancreas is damaged.[9]

An endoscopic ultrasound is an outpatient procedure and should take less than 45 minutes. The test can be performed with the patient either conscious or unconscious; if you’re conscious, the medical staff will give you medication to reduce the discomfort. -

3Talk to your doctor about getting a CT scan. A CT scan is usually not necessary for diagnosing EPI, but in some cases it may be helpful. If your doctor decides that a CT scan is needed in helping to diagnose your EPI, you’ll be referred to a clinic with a CT machine.

For the scanning procedure, you’ll need to lie on your back in the large donut-shaped CT machine; you’ll be slid into the machine as it scans your abdomen.[10]

A CT scan will provide X-ray images of your abdominal region, and will help doctors detect signs of chronic pancreatitis, one of the most common causes of EPI.[11]- In some cases, you’ll be asked to drink a tea-like mixture called a “contrast” in order to highlight different parts of your internal abdominal structure.[12]

- Depending upon your doctor’s preference and the medical equipment available, you may be given an MRI scan or an MRCP scan in the place of a CT scan. All three tests serve largely the same purpose.

Warnings

- Alcohol abuse is a common cause or contributing factor in the development of EPI. If your EPI stems from overuse of alcohol, you will need to stop drinking in order to successfully treat and manage your EPI. If you are unable to stop drinking on your own, talk to your doctor about getting treated for alcoholism.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ http://www.uptodate.com/contents/exocrine-pancreatic-insufficiency

- ↑ https://labtestsonline.org/understanding/conditions/pancreatic-insuf/start/1

- ↑ https://labtestsonline.org/understanding/conditions/pancreatic-insuf/start/1

- ↑ https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-017-0783-y

- ↑ http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/epi-diagnose#1

- ↑ http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/epi-diagnose#1

- ↑ http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/epi-diagnose#1

- ↑ https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2121028-workup

- ↑ http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/epi-diagnose#2

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...