This article was co-authored by Trudi Griffin, LPC, MS. Trudi Griffin is a Licensed Professional Counselor in Wisconsin specializing in Addictions and Mental Health. She provides therapy to people who struggle with addictions, mental health, and trauma in community health settings and private practice. She received her MS in Clinical Mental Health Counseling from Marquette University in 2011.

There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 37,590 times.

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) occurs in children, and affects six to 10% of all children.[1] It can be challenging to parent a child with ODD, as it may feel like there’s a constant power struggle and you just can’t seem to get along. It’s important to understand your child and to make any necessary adjustments in how you approach managing behavior.

Steps

Understanding Your Child’s Behavior

-

1Identify symptoms of ODD. Children with ODD tend to exhibit certain behaviors that identify ODD, usually beginning in preschool and almost always presenting before the early teen years.[2] While all children experience behavior difficulties, a child with ODD will display a "frequent and persistent pattern"[3] of hostile and disobedient behavior. If you identify four or more of the following behaviors in your child that cause problems at home, school, and other environments, which have lasted six months or more, take your child to a therapist to see if he fits a formal diagnosis:[4] [5]

- Loses temper often

- Argues frequently with adults

- Refuses to comply with requests from adults

- Deliberately annoys people, is easily annoyed by others

- Blames others for his mistakes or misbehavior

- Is angry or resentful

- Is spiteful or vindictive

-

2Notice a tendency toward victimhood. Children with ODD often experience themselves as victims, and believe that their actions of punching a wall or hurting another child are justified.[6] Remind the child that she is allowed to feel angry, resentful, and upset. She may even be a victim in a situation. However, often the reaction is more severe than the original offense.Advertisement

-

3Discuss your child's reactions. While your child may be rightfully upset, he is in charge of his behaviors and reactions. Nobody made him react in a harmful or negative way; he chose it. Acknowledge that bad things happen, but that it’s his decision how to respond to things, even when something unfair happens.

- Ask your child, “If someone is mad at you, is it okay if she hits you? What about if you’re mad at someone? Can you hit him? What’s the difference?”

-

4Acknowledge the need to be in control. Children with ODD often will go to extreme lengths to feel in control. You may start by discussing your child hitting his sibling, and end up in a power struggle about something unrelated. Instead of engaging the struggle, disengage from the situation.[7] You can steer the conversation back to the original point, or you may choose to walk away.

- Recognize when your child is arguing to defend himself or whether it is coming from a place of wanting power.

-

5Talk about constructive ways to handle a difficult situation. Your child doesn't just need to know how not to respond, but how to respond well. You can discuss or even role-play situations to help them learn constructive responses. Talk about...

- Taking deep breaths or counting to calm down

- Setting boundaries, such as "I need some alone time" and "Please don't touch me."

- Using "I" language

- What to do when someone else doesn't respect their boundaries or feelings

- Getting help when they are upset or confused

Adjusting Your Parenting Techniques

-

1Learn how to communicate effectively with your child. When trying to communicate with your child — whether it be a request, a reprimand, or praise — there are ways to communicate that are helpful and productive, and ways that will impede communication and possibly trigger bad behavior.

- Try to communicate calmly, clearly, and using short, to-the-point explanations. State what you want and expect using direct language.

- Make eye contact and maintain relaxed or neutral facial expressions, gestures, and posture.

- Ask your child questions and listen to his answers. Discuss what is happening in the present, not things he did in the past, and try to be solution-oriented.

- Do not lecture your child, yell, name call, bring up old problems, make assumptions about your child or his behavior, or use negative body language.

-

2Respond without anger. While it’s difficult to remove your own emotions from a situation, do your best to respond to your child without anger. State what has happened, why it’s not okay, and what needs to change. Follow through with any consequences relating to the behavior. Then, remove yourself from the situation and don’t engage in any conflict.[8]

- If you find yourself becoming angry, take some deep breaths to help center yourself, or repeat a phrase that helps you such as “I am calm and relaxed”.[9] Take some time before responding in order to avoid saying anything you may regret.

-

3Step away from the blame game. Don’t blame your child (“My child is ruining my life. I have no time for myself because I’m always disciplining her”) and don’t blame yourself (“If only I was a better parent, my child wouldn’t act like this.”) If you find yourself caught up in these thoughts, take a step back and acknowledge how you are feeling. Remember that your child is not responsible for your emotional well-being; only you are responsible for how you feel.[10]

- Take responsibility for your own feelings and actions, and show yourself to be a role model for your child.

-

4Be consistent. Inconsistent parenting can be confusing for a child. If a child sees an opportunity to get something that they desire, they will most likely take it. They may try to wear down your defenses in order for you to give in and say yes. When in conflict, be consistent in how you respond. Be clear in your expectations and strong in your willpower to enforce the guidelines.[11]

- Create a positive behaviors and consequences chart, which lets your child know what will happen with certain behaviors. Being clear and consistent is helpful for knowing what to expect for both you and your child. Reward good behavior and respond to bad behavior with appropriate consequences.

- If your child tries to wear you down, be clear. Say "No means no" or "Do I look like the kind of dad who will change his mind if you keep asking?" Try a simple, business-like response, such as, "This is not up for discussion," or, "I'm not arguing over this. This discussion is over."

-

5Adjust your thoughts. If you come into a discussion assuming your child is trying to annoy you or cause a problem, this will color how you respond. It’s natural to push back when someone pushes against you, even when it’s your child. Don’t expect your child to correct these behaviors on his own, he needs guidance. When you start to have negative thoughts about your child, replace them with more positive ones.[12]

- If you find yourself thinking, “My son is always trying to start a fight and never knows when to let go”, replace that thought with, “Every child has strengths and difficulties. I know with my consistent effort, I will help my child build the skills he needs to express himself productively.”

-

6Identify family and environmental stressors. Consider what sort of home life your child has. Is there constant fighting or is a family member struggling with substance abuse problems? Do you spend very little time with your child, or does she watch excessive amounts of TV or play video games for hours? Identify both obvious and more subtle ways the home environment may be negatively affecting your child, then work to change those things.

- Consider limiting TV or gaming time, having mandatory family dinners, and seeking counseling if you and your partner are constantly fighting. If there is substance abuse or a mental health disorder in the family, help that person begin treatment.

- Other potential environmental or family stressors include economic stress, parental mental illness, severe or harsh punishment, multiple moves, and divorce.

-

7Help identify emotions. Your child may experience anger or frustration but not know how to express these emotions in a positive or constructive way. If you notice your child is angry, label the emotion for them. Say, “It seems like you’re angry.” Identify feelings in others and in yourself. Say, “Sometimes I feel sad, and when I feel sad, I don’t want to talk to people and I keep my head down.”[13]

- Talk about how feelings can be expressed. For instance, say, “How can you tell when someone is upset? When do you notice when someone is happy? What does it look like when someone is mad?” Talk about ways that your child experiences and expresses emotions.

-

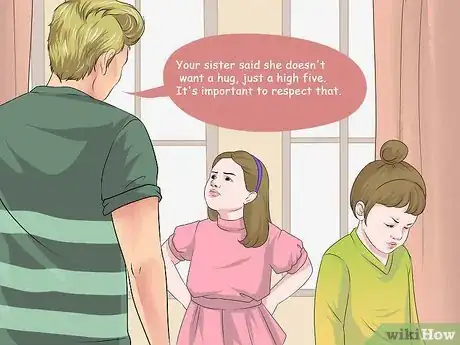

8Emphasize the importance of boundaries and respect. Make it clear that both your child and other people have the right to set boundaries, and to have others respect those boundaries. Learning the basics of consent can help your child recognize why hitting, poking, or kicking others is not okay.

- Enforce others' boundaries as needed. For example, "Your sister said she doesn't want a hug, just a high five. It's important to respect that."

- Enforce your child's boundaries as well. For example, if another child plays with your daughter's hair, even after your daughter has asked them to stop, give the other child a stern look and say that this is not okay.

Reaching Out for Help

-

1Begin treatment as soon as possible. Children with ODD can improve — studies have shown up to 67% of children diagnosed with ODD will be symptom-free within three years if they receive treatment.[14] The sooner you address and begin to treat ODD and any co-existing conditions, the better your child's chances are of improving.

-

2Seek a therapist for your child. If you’re having problems getting along with your child, chances are your child is struggling, too. While outwardly your child may be misbehaving, inwardly they may not know how to express their wants and desires in a way that is easily received. A therapist can help your child express himself in a more conducive way. They can help your child understand emotions, express emotions in a constructive way, and work through anger.

- Behavior therapy serves to help children unlearn negative behaviors, and replace them with more positive behaviors. Therapy often involves parents to help enforce the new learned behaviors at home.[17]

- Therapy may help your child learn problem solving skills, empathy, social skills, and help reduce aggressive behaviors.

- See if there is a social-skills program at the child's school or somewhere nearby. This program helps teach children to interact with their peers in a more positive way as well as help them improve school work.[18]

-

3Treat co-occurring mental health conditions. Often, children with ODD will also have another emotional problem or disability, such as anxiety, depression, or ADHD.[19] If you suspect your child may have one of these disorders, make an appointment with a therapist in order to discuss a possible diagnosis. A child will not make progress with his ODD unless the co-existing disorder is treated as well.[20]

-

4Attend parent-management training programs and family therapy.[21] While you may have found it less difficult to handle your other children and their problems, you may find yourself at a loss in how to parent your child with ODD. You may find it helpful to adjust your approach to parenting altogether. A parenting class can be beneficial in creating structure to your approach to parenting.

- You may learn different ways to approach your child’s behavior, systems for managing behavior, and find support with other parents who are struggling with their kids.[22]

- Family therapy can help the entire family learn how to interact positively with the person with ODD, and can give other family members a voice. It can also help educate family members about ODD.

-

5Listen to teens and adults who experienced ODD. Learn about what their parents did that helped them the most, and what they would like you to know as a parent. Because they have been in your child's position, they can offer great insight on how to handle things well.

-

6Join a parent support group. A support group can offer help in a way that other resources cannot. Meeting with other parents who encounter similar struggles can be a relief as well as a way to share struggles and inspirations. You can begin friendships with other parents who encounter similar difficulties, and offer support to one another.[23]

- Check out online resources as well, such as Incredible Years, Center for Collaborative Problem Solving, and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT).[24]

-

7Supplement treatment with medication if necessary. Medication alone is not a suitable treatment for ODD, but it can help treat co-occurring mental health conditions or reduce some of the more severe symptoms of ODD.[25] Make an appointment with a psychiatrist and discuss whether or not medication is the right choice for your child.

- Before pursuing medication, consider the following: whether the child has had a physical and psychiatric evaluation, if all other treatments have been attempted, possible side effects (weight gain, affecting growth, etc.), how medication will be given at home and at school, how to talk to the child about the medication and side effects, how to monitor for side effects.

Expert Q&A

-

QuestionDo I need a referral to see a child psychologist?

Klare Heston, LCSWKlare Heston is a Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker based in Cleveland, Ohio. With experience in academic counseling and clinical supervision, Klare received her Master of Social Work from the Virginia Commonwealth University in 1983. She also holds a 2-Year Post-Graduate Certificate from the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland, as well as certification in Family Therapy, Supervision, Mediation, and Trauma Recovery and Treatment (EMDR).

Klare Heston, LCSWKlare Heston is a Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker based in Cleveland, Ohio. With experience in academic counseling and clinical supervision, Klare received her Master of Social Work from the Virginia Commonwealth University in 1983. She also holds a 2-Year Post-Graduate Certificate from the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland, as well as certification in Family Therapy, Supervision, Mediation, and Trauma Recovery and Treatment (EMDR).

Licensed Social Worker Usually not, but you will if your insurance company requests it. If this is the case, start with the child's pediatrician. If testing will be required, make sure the person you select has the requisite training.

Usually not, but you will if your insurance company requests it. If this is the case, start with the child's pediatrician. If testing will be required, make sure the person you select has the requisite training.

References

- ↑ https://psychcentral.com/blog/4-ways-to-manage-oppositional-defiant-disorder-in-children

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/oppositional-defiant-disorder/basics/symptoms/con-20024559

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/oppositional-defiant-disorder/basics/symptoms/con-20024559

- ↑ https://psychcentral.com/blog/4-ways-to-manage-oppositional-defiant-disorder-in-children#1

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/oppositional-defiant-disorder/basics/symptoms/con-20024559

- ↑ https://psychcentral.com/blog/4-ways-to-manage-oppositional-defiant-disorder-in-children#1

- ↑ https://www.empoweringparents.com/article/odd-kids-and-behavior-5-things-you-need-to-know-as-a-parent/

- ↑ https://psychcentral.com/blog/4-ways-to-manage-oppositional-defiant-disorder-in-children#1

- ↑ http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/controlling-anger.aspx

- ↑ https://www.empoweringparents.com/article/odd-kids-and-behavior-5-things-you-need-to-know-as-a-parent/

- ↑ https://psychcentral.com/blog/4-ways-to-manage-oppositional-defiant-disorder-in-children#1

- ↑ https://www.empoweringparents.com/article/odd-kids-and-behavior-5-things-you-need-to-know-as-a-parent/

- ↑ http://msue.anr.msu.edu/news/help_young_children_identify_and_express_emotions

- ↑ https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/resource_centers/odd/odd_resource_center_odd_guide.pdf

- ↑ https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/resource_centers/odd/odd_resource_center_odd_guide.pdf

- ↑ http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Conduct-Disorder-033.aspx

- ↑ https://www.mentalhelp.net/articles/treatment-of-oppositional-defiant-disorder/

- ↑ https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/resource_centers/odd/odd_resource_center_odd_guide.pdf

- ↑ http://www.kidsmentalhealth.org/children-conduct-disorder-oppositional-defiant-disorder-odd/

- ↑ http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-With-Oppositional-Defiant-Disorder-072.aspx

- ↑ https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/resource_centers/odd/odd_resource_center_odd_guide.pdf

- ↑ http://www.healthguidance.org/entry/16109/1/Parenting-Classes-Pros-and-Cons.html

- ↑ https://childmind.org/article/how-parent-support-groups-can-help/

- ↑ https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/resource_centers/odd/odd_resource_center_odd_guide.pdf

- ↑ https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/resource_centers/odd/odd_resource_center_odd_guide.pdf

-Step-17-Version-2.webp)

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...