This article was co-authored by Alexander Peterman, MA. Alexander Peterman is a Private Tutor in Florida. He received his MA in Education from the University of Florida in 2017.

There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 31,011 times.

Writing can be an art form. In creative writing, especially, the goal is to paint a vivid picture in your reader’s mind. As a writer, you may be alone at your desk with nothing but a computer and a lamp, but you can use your imagination to build whole worlds. There are a variety of literary techniques, from simile to metaphor, to help you pull those worlds from thought down onto the page in front you and eventually into your reader’s minds.

Steps

Using Imagery

-

1Work from your personal experiences. In order to create a vivid picture with your writing, you should have a clear vision of what you are describing. That means that, in most cases, you should describe people, places, or things that you have actually seen or experienced in person.

- For example, it’d be pretty difficult to describe the Rocky Mountains if you’ve never actually seen them or spent time in them.

- In some cases, you may be able to do sufficient research to describe something you haven’t personally experienced.

- An exception to the rule is if the thing you are describing is made up. In that case, do your best to describe it in detail so readers are able to picture it in their own minds.

-

2See the image in your own mind first. If you can’t see the scene you’re trying to write about in your own mind, you can’t expect your reader to see it. Close your eyes, or keep them open—whichever works for you—and imagine everything that is going on in the scene you want to describe in your writing.[1]

- For example, if you’re going to describe a house, start by picturing the house in your mind. Pictures the details of the house: is it small or big? Wooden or brick? New or crumbling? The more details about the house you can picture in the mind, the more you’ll be able to convey the scene to your reader.

- Not everyone has a good “mind’s eye.” In other words, not everyone can see clear pictures in their minds. If you have a dull mind’s eye, don’t fret: you can likely still imagine scenes in your mind—you just don’t see them in clear pictures.[2]

- Your reader will never see exactly the same scene you see in your mind. That’s OK. That’s the beauty of reading: each person uses their own experiences and imagination to fill in the gaps.

Advertisement -

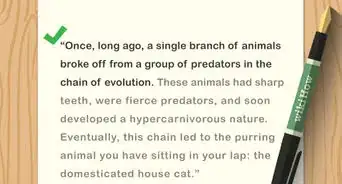

3Describe what you see. Take the image in your mind and write down the descriptor words that you want to focus on. You can begin by writing down more about the scene than you’ll keep in your final sentence.

- Pay attention to the details you want the reader to notice and ignore the unimportant details. If you describe the whole scene in equal detail, the reader won’t know they you wanted them to focus on one specific thing in the scene.

- For example, if you’re writing about a tree you want to focus on the details of the tree and leave out too much detail about the tree’s surroundings. “The dull-gray birch tree swayed in the breeze,” calls attention to the tree. “The landscape was mostly barren, with a few tall trees jutting out of the yellow grass,” calls attention to the landscape as a whole rather than a particular tree.

-

4Explain what you hear. Pay attention to all of the sounds happening in the scene. In ordinary life we often times tune out sounds. As a writer, it’s your job to get the reader to tune in to the sounds you want them to hear. If there are any sounds you want the reader to pay attention to, write them down.

- For example, “The screech of an owl pierced the silence in the field.”

- Consider all of the available sounds in your scene. For example, if you’re describing a busy apartment complex, you might hear people talking or arguing through the walls, a car honking in the parking lot, or the sound of muffled music coming from the apartment below. All of these sounds help paint the scene in your reader’s mind.

-

5Describe what you touch. This is important if you’re describing a character’s experience of touching an object. For example, “Bruce picked up the rock and held it. From the ground it had looked smooth, but in his hands it was rough and covered in a slimy film.”

- Try to think of any tactile sensations that will help your reader identify with the scene. If your character is in a dentist’s office, you might talk about the feel of the vinyl arms of the dentist’s chair, or the vibration of the drill on the patient’s teeth.

-

6Describe what you taste. Do this by considering the context of your scene. Did your character just wake up? You could describe the slimy taste of unbrushed teeth.

- Taste can sometimes be used to describe a setting. For example, if you’re writing about a coal mine you might say, “The workers arrived every morning at 4 a.m., and each morning they were greeted with thick curtains of black dust and soot that coated their tongues, so that they could taste their own deaths approaching day-by-day.”

-

7Explain what you smell. Smell is the strongest sense associated with memory, so describing smells is a good opportunity to get your reader to picture a scene in their minds. For example, you could write a descriptive sentence like: “A fire burned in the distance and Robin could smell the that it was seeded with pine and oak.”

- Think of all the little smells that we notice on a day-to-day basis. If your character is walking through a busy New York street, you might describe the smell of hotdogs or flowers, or the sudden whiff of garbage or sewage as they turn a corner.[3]

Using Other Literary Devices

-

1Add metaphor. Metaphors compare the idea you are writing about directly to another idea in a way that brings your idea to life. Metaphors offer you unlimited creativity in your writing and can turn a bland sentence into a colorful image.[4]

- There is almost no limit to how you use metaphors. Don’t be afraid to step outside the box (that’s a cliché metaphor!).

- For example, if your character is depressed, you might write, “In his depression, it was always 3 a.m. in his mind.” In this example the writer is describing depression and comparing it to the feeling of being awake at 3 a.m. all of the time. In describing scenery, you might write, “The birch trees were white fire, lit up by the setting sun.” In this example, the writer is describing the birch trees and comparing their color to white fire.

-

2Try a few similes. Similes are a kind of metaphor that uses indirect comparisons with words like “like” and “as.”[5]

- To emphasize a character’s affectation, you could write, “He waived his finger at her like a magic wand.” To call your reader’s attention to quiet in a scene, you could write, “The night was as still as the surface of the moon.”

- With similes (and metaphors), it’s important that the comparison conveys something meaningful. The best way to describe this concept is with a bad metaphor. “He waited for her like a man waiting for a roast beef sandwich,” is a simile, but it’s hard to see what meaning if being conveyed since it isn’t obvious what a man waiting for a roast beef sandwich is like.[6]

-

3Use personification. Personification gives human qualities to an animal or object. This can be a useful tool to help paint a picture in your reader’s mind and bring an animal or object to life.[7]

- An example of personification is, “The shadows of the trees danced over the snow.”

- Another example is, “The cat glared at me from her perch.”

-

4Don’t overdo it. Literary devices can greatly enrich your writing, but they can also be distracting if used too often. Limit your use of metaphor, simile, and personification to places where it will help the reader understand the picture you and trying to paint.[8] Avoid using clichés as well.

- Here’s an example of too much metaphor and simile: “Her face was a red beet of rage. She rushed at him like a bullet from a gun and struck his frozen face. He fell back as though struck by a train.”

Working with the Rules of Writing

-

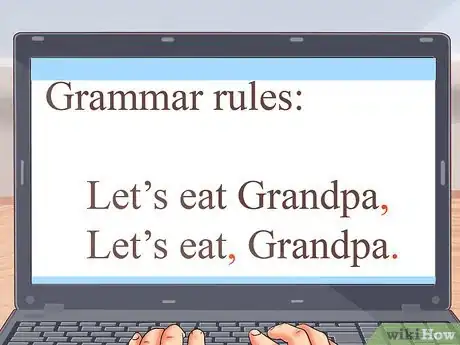

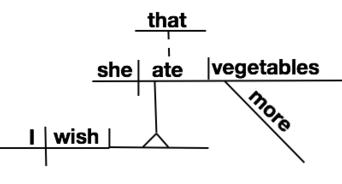

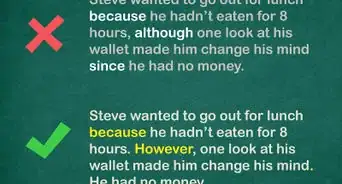

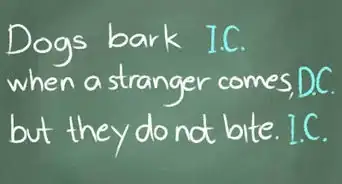

1Obey the rules of grammar. Grammar rules exist for a reason: they make writing easier to understand so the reader doesn’t have to work to figure out what you’re trying to say. Grammar rules also help avoid ambiguity. For example, consider the following sentences: “Let’s eat Grandpa,” and “Let’s eat, Grandpa.” Each sentence has a different meaning thanks to the absence or presence of the comma.[9]

- You don’t need to be a grammar expert to write good sentences, but you do need to have at least an intuitive feel for the rules of grammar. A good way to check if you’re using grammar correctly is to read a sentence that you’ve written and ask yourself, “would this sentence make sense to me if I hadn’t written it?”

- Don’t be afraid to refresh your grammar skills if you need to.

-

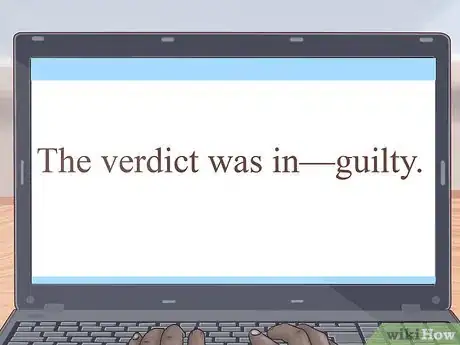

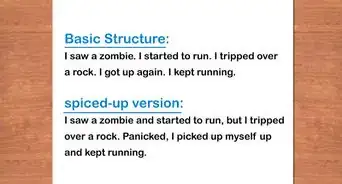

2Use style to emphasize your writing. Two sentences can convey the same information but have a different feeling depending on how they use grammar. Consider this pair of examples: “The verdict was in. He was guilty,” and “The verdict was in—guilty.” The second sentence empathizes “guilty” more than the first sentence.[10]

- The most recommended book on style out there is still Strunk and White’s “The Elements of Style.” Pick up a copy if you need some inspiration.[11]

-

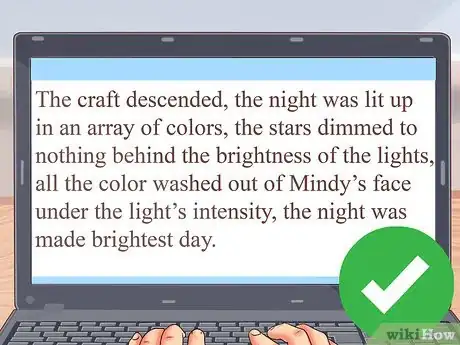

3Break the rules of grammar occasionally! The cliché that rules are made to be broken applies well to grammar. You shouldn’t break the rules before knowing them. But ignoring strict grammatical perfection can add color and feeling to your writing.[12]

- Most authors break the rules of grammar from time-to-time, so you’ll be in good company. In fact, breaking the rules of grammar can add style and flourish to your writing. The following phrase breaks the rules of grammar - notice the lack of conjunctions, for instance - but presents vivid imagery that couldn’t be achieved by following the rules: “The craft descended, the night was lit up in an array of colors, the stars dimmed to nothing behind the brightness of the lights, all the color washed out of Mindy’s face under the light’s intensity, the night was made brightest day.”

- You still want your writing to make sense, so don’t break a grammatical rule if it will make your writing difficult to read. The goal of grammar—and the lack thereof—is to make the reader understand what you’re trying to say. For example, the following example makes it hard to understand what the author is trying to say: “She bit into the apple a cold thing crying not knowing why.”

Avoiding Bad Style

-

1Limit your use of detail and adjectives. While you want to provide enough detail to paint a picture in the reader’s mind, you don’t want to provide so much that the plot or action of the story becomes secondary. In the same vein, though adjectives are certainly important in descriptive writing, don’t over use them. Doing so slows down the pace of the story and can cause your reader to become disinterested.

- Here’s an example of using too many adjectives: “The mare’s coat was soft, silky, smooth, and shiny.” This could be phrased as, “The mare’s coat was silky and shiny,” to convey the same message.

-

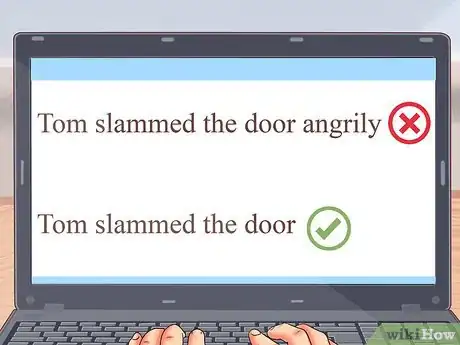

2Don’t overuse adverbs. Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs and usually end in -ly. The problem with adverbs is that they show the reader you’re afraid of not getting your point across. You want your writing to be clear, but you don’t want to spell everything out for the reader—otherwise there’s no room for the reader’s imagination.[13]

- Try to let your descriptions of things speak for themselves, without the need for adverbs. For example, the sentence “the front yard was covered in car parts,” conveys the same information as “the front yard was completely covered in car parts,” but the second sentence is redundant. If the yard is covered, it’s covered.

- Watch for adverbs in dialogue attribution. Authors use adverbs in dialogue attribution when they’re afraid the reader doesn’t understand the characters in the story. For example, if two characters are having an argument and you have to write, “Tom slammed the door angrily,” you probably haven’t done enough work to convince the reader that there’s an argument going on. “Tom slammed the door,” conveys the same meaning if the reader understands the character’s motivations.

- Sometimes using adverbs makes sense. The key is not to overuse adverbs; you can still use them if they help the reader. For example, if your story takes place in London, it might be OK to say, “It was especially dreary that day,” since it’s always kind of dreary in London.

-

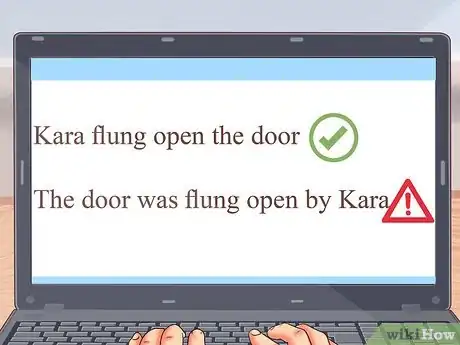

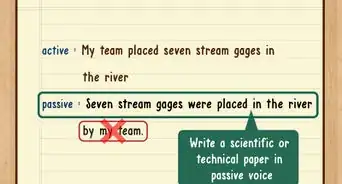

3Watch out for the passive voice. The passive voice sucks energy and agency out of your writing. Simply replacing every instance of passive voice with the active voice will likely improve your writing.[14]

- One use of passive voice is where an object has something done to it instead of an actor—an agent—doing something to an object. For example, “Kara flung open the door,” and “The door was flung open by Kara,” convey the same information, but the former is active. In other words, it has Kara doing something rather than having something done by Kara.

- Another use of passive voice is where the actor is left out altogether. “Mistakes were made,” is a good example. That sentence hardly paints a picture at all. What mistakes? And who made them? Instead, you could say: “Donald’s career was full of mistakes: small mistakes—typos, missed deadlines, not-so-sick sick days—, and big mistakes—lying in court, covering up crime’s for his rich clients, bribing elected officials.”

-

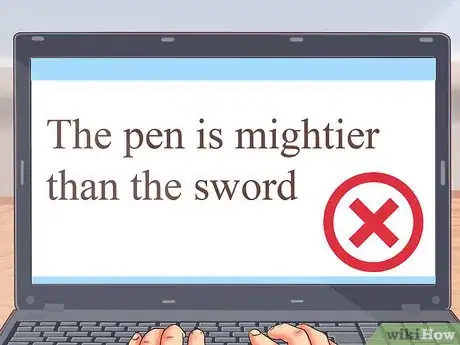

4Avoid clichés. Some clichés are obvious. “The pen is mightier than the sword,” or “You really struck out this time.” Others are so embedded in our language that we hardly notice them. “He was running on empty,” or “Danny needed to blow off some steam.” Clichés are dangerous because they oftentimes feel very descriptive; the problem is that they’re so overused that they’re no longer effective as calling up an image in readers’ minds.[15]

- Clichés mostly pop up when you’re trying to think of metaphors and similes. For example, you might describe the night as “black as pitch,” or a character as “boiling over with rage.” Watch out for these clichés, and try to use your imagination to come up with original metaphors and similes. For example, you could write, “she walked outside and the dark fell over her like a blanket,” or “Danny’s anger was an iron core just short of nova.”

- It’s OK to use clichés if you do so with a purpose. Maybe one of your characters is meant to be very cliché, or maybe you’re using a cliché ironically. The important thing is to be aware that you’re using clichés and you know why you’re using them.

References

- ↑ http://thewritepractice.com/paint-with-words/

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/news/health-34039054

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/brain-babble/201501/smells-ring-bells-how-smell-triggers-memories-and-emotions

- ↑ http://www.enchantingmarketing.com/metaphor-examples/

- ↑ http://literarydevices.net/simile/

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books/about/On_Writing.html?id=d999Z2KbZJYC

- ↑ https://literarydevices.net/personification/

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books/about/On_Writing.html?id=d999Z2KbZJYC

- ↑ http://theweek.com/articles/466720/7-grammar-rules-really-should-pay-attention

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books/about/On_Writing.html?id=d999Z2KbZJYC

- ↑ http://www.quickanddirtytips.com/education/grammar/strunk-and-white

- ↑ http://thewritepractice.com/break-grammar-rules/

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books/about/On_Writing.html?id=d999Z2KbZJYC

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books/about/On_Writing.html?id=d999Z2KbZJYC

- ↑ http://www.be-a-better-writer.com/cliches.html