There is a really excellent blog post on Washi's blog titled "Anime Production - Detailed Guide to How Anime is Made and the Talent Behind it!" that covers pretty much the entire process that includes references from Studios like I.G., AIC, and Sunrise.

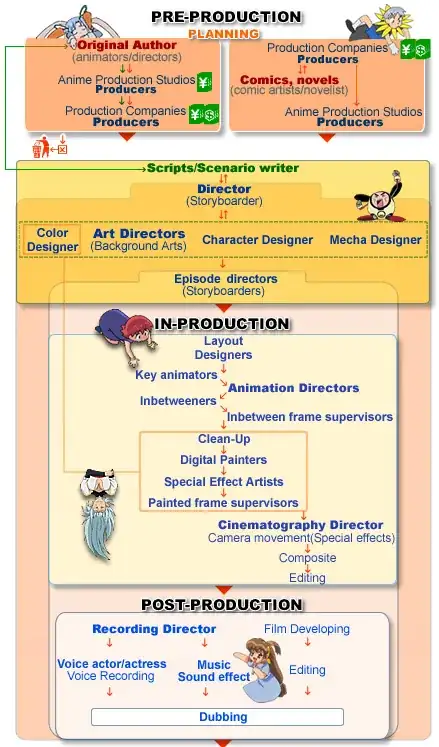

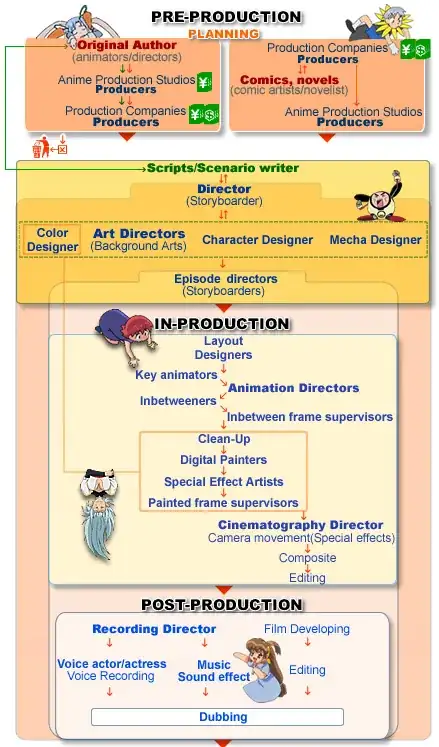

Here's a flowchart from the link that describes the process:

So you have the pre-production and planning phase, which can happen either from an original author or a production company:

This process depends on who’s pushing for an idea and who is backing it up, it can be animation studios themselves along with sponsors, but many anime are adaptations of manga or light novels, in which case, publishers front costs (including the costs of having it shown on TV stations). The production company (e.g Aniplex) gathers staff, sponsors, and looks at advertisement and merchandise. While many people describe studios as being cheap, only around half the budget is often given to the anime studio, with the rest going to broadcasters and other contributing companies. The broadcast costs are surprisingly high – according to blogger, ghostlightning – at about 50 million yen for a late-night timeslot across 5-7 stations for a 52 episode series. You can see why anime can be an expensive business. For example, Full Metal Alchemist, which had a 6pm Saturday slot had a total budget of 500 million yen (before additional costs).

This part of the processes then becomes mostly planning, designs, and putting together the staff. When it's time to create the first episode, then the prodcution phase starts:

The first step is to write the episode scripts. Following the episodes synopsis/plans, the full scripts are written, by either one person for the whole series or by several different writers based on the outlines from the overall script supervisor (staff credit: series composition). The scripts are reviewed by the director, producers, and potentially the author of the original work before being finalised (after 3 or 4 drafts, often). The episode director, supervised by the overall director then takes this backbone of the episode and must plan out how it will actually look on screen. While the director has the final say and is involved at production meetings, the episode director has the most hands-on involvement in developing the episode. This stage is expressed as a storyboard (a visual script), and the storyboard marks the beginning of actual animation production.

Storyboarding:

Often the storyboard is created by the director, this means an episode is truly the vision of that director. But usually, mainly in TV-anime, separate storyboarders are used to actually draw them. This is because storyboards usually take around 3 weeks to do for a normal length TV-anime episode. Art meetings and production meetings are held with the episode director, series director and other staff about the episode should look. Storyboards are drawn on A-4 paper (generally) and contain most of the vital building blocks of an anime – the cut numbers, actor movements, camera movements such as zooming or panning, the dialogue (taken from the screenplay) and the length of each shot (or cut) in terms of seconds and frames (which we’ll explain later). Because the number of drawings available for an episode is often fixed for the sake of budget management, the number of frames is also carefully considered in the storyboards. The storyboards are roughly-drawn and are really the core stage of deciding how an anime will play out. Cuts refer to a single shot of the camera and an average TV-anime episode will usually contain around 300 cuts. More cuts don’t necessarily imply a better quality episode, but it will generally mean more work for the director/storyboarder.

The post then covers the layout and the animation process, then finally, the composition and filming:

It is commonplace for the frames to be completed on a computer. After they are drawn and checked, they are digitized. Once they are on the computer, they are painted with a specified color palette by painting staff (generally a low paid job). They use the shading lines drawn by the key animators to do the shading colours. This digital equivalent of the ‘ink & paint’ stage of production, which used to be done by hand, has allowed some more interesting visual styles to come through in the colouring, such as the use of gradient shading or even textures. These would have been too difficult to do back in the day. It has also saved considerable time and money in the process. These become the final “cels” that go into the animation.

Once all the frames are coloured and finished, they can be processed as animation using a specialized software package. “RETAS! PRO” is used for approximately 90% of anime currently aired in Japan (for drawing sometimes too)! Before the use of digital ‘cels’ (digicels), drawings (printed onto cels) were actually filmed over backgrounds. Now, cuts are completed digitally, and the background art can be added on the computer. Initially, when digicel was first being picked up by studios (around about 2000), it had real problems matching the fineness of detail in hand-drawn and painted cels. But nowadays, anime studios have really perfected the digital cel, giving us anime with just as much detail and more vibrant colouring. The digicel age has now streamlined the production process such that repeated cels and clip/recap episodes are basically a thing of the past. Some still prefer the rougher look of pre-2000, but I’ve certainly moved on.

...

After compositing is completed for all the cuts, they have to be to the timing required for broadcast, so that the episode doesn’t lag overtime. With the completion of the editing step, the episode moves out of production and into post-production. I won’t go into much detail on this, but it essentially encompasses adding sound (dubbing), both the music and the voice recordings, and final editing (cutting the episode with space for advertisements). Visual effects may also be added at this late stage too.